In this report, we briefly review the history of how MAiD was legalized in Canada, the ableist foundation of Canada’s new legislative framework, and the dangerous gaps it leaves in the law. We then suggest amendments to Canada’s law and practice to counter the ableist mindset that brought Canada’s MAiD law to where it is today.

When the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the Criminal Code prohibitions on assisted suicide in the 2015 Carter case, it overturned years of legal, medical, and ethical precedents.[i] Parliament responded in 2016 with Bill C-14,[ii] which amended the Criminal Code and established a framework in which doctors could legally end the lives of some of their patients.[iii] Doctors were permitted to cause a patient’s death or assist a patient’s suicide by administering a lethal injection (consensual homicide) or by prescribing a lethal drug for the patient to self-administer (assisted suicide). In Bill C-14, consensual homicide and assisted suicide were limited to those whose natural death was “reasonably foreseeable” – in other words, for those who were suffering terribly from an incurable condition as they neared their natural death.

So-called “medical aid in dying” or “MAiD” was, at first, for those who were dying. Since Bill C-7 passed in 2021, however, MAiD is on offer to people who are not dying, to people with disabilities or chronic illnesses that are not terminal. The federal government erred when it weakened what were already inadequate protections for vulnerable Canadians with diseases or disabilities.

Inadequate safeguards

The Supreme Court of Canada, in its 2015 ruling in Carter, began and ended its judgment with statements about how narrow the scope of their judgment was intended to be.[iv] (As ARPA Canada and others have consistently maintained, Carter did not force Parliament to permit euthanasia or assisted suicide at all.[v]) When Bill C-14 was passed in 2016, decriminalizing assisted suicide and euthanasia, the bill required a five-year review of the legislation to ensure safeguards were functioning well and vulnerable people were adequately protected. Before this review occurred, however, a lower-court judge in Quebec ruled[vi] that people with disabilities who were not dying should also be eligible for MAiD.[vii] Rather than appeal this decision and complete the required five-year review, the federal government worked instead to further liberalize MAiD.

In addition to legalizing MAiD for persons who are not dying, Bill C-7 eliminated waiting periods for persons whose natural death is “reasonably foreseeable”,[viii] (a vague term that certain doctors have interpreted as meaning the patient is likely to die within a decade[ix]), and within two years will automatically expand access to those suffering solely with a mental illness.[x] Bill C-7 also cut the requirement for witnesses down from two to one and made it easier to qualify as a witness.[xi]

Justice Lynn Smith, the trial judge in Carter, ruled in 2012 that the “inherent” risks of legalizing MAiD could be “substantially minimized” (although not eliminated) through a “carefully-designed system imposing stringent limits that are scrupulously monitored and enforced.”[xii] Justice Smith asserted this despite evidence that safeguards often go ignored in every jurisdiction that has legalized MAiD.[xiii] In a stunning rebuke of Justice Smith, the High Court of Ireland ruled in 2013 that “the Canadian court reviewed the available evidence from other jurisdictions with liberalized legislation and concluded that there was no evidence of abuse. This Court also reviewed the same evidence and has drawn exactly the opposite conclusions.”[xiv]

Instead of a strictly limited, scrupulously monitored system, the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers encourages health care providers to bring up MAiD as an option for anyone who may be eligible.[xv] MAiD is funded in every province and patients who are suffering have greater access to MAiD than to social supports, palliative care, or psychological counseling. MAiD assessors and providers have developed their own guidelines around acceptability, with plenty of leeway for personal preference.[xvi] At industry conferences, practitioners faced with challenging cases are encouraged by MAiD leaders to ask a colleague, not a lawyer, about the legality of ending a particular patient’s life.[xvii] When a MAiD death is questioned, law enforcement may try to pass off responsibility to the Ministry of Health instead of investigating a homicide.[xviii]

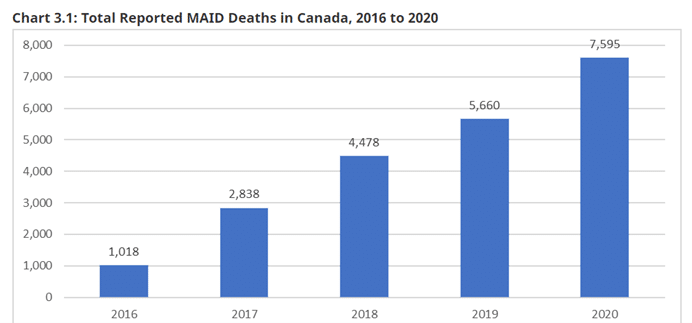

Canada’s system for MAiD meets none of the stringent criteria for minimizing risks that Justice Smith envisioned. Predictably then, Canada has seen a major increase in recorded MAiD deaths each year.[xix]

The safeguards in Bill C-14 (2016) were never enough to ensure the safety of patients and the accountability of providers. The further weakening of safeguards in Bill C-7 (2021) will have serious consequences for vulnerable Canadians.

MAiD and ableism

Bill C-14, and then C-7, codified the principle that it is permissible to intentionally kill a person who asks to be killed, provided they no longer possess the qualities or capabilities that society deems necessary for sufficient “quality of life.” In other words, it is okay for some people – particularly medical doctors – to make value judgements about whose life is worth living and to offer either suicide assistance or suicide prevention based on their assessment[AS2] .

The foundational ethic of Western law and human rights cares for – and does not kill – the weak, sick, disabled, and elderly.[xx] We find this in the biblical sixth commandment[xxi] and in the Hippocratic Oath.[xxii] We find it in the prohibitions on killing found in every nation’s criminal laws today, in the continued prohibition on assisted suicide in most nations, and in the continued prohibition in Canada on counselling a person to commit suicide.[xxiii]

Yet Bill C-7 created an elitist, ableist system that ignores the concerns of “voices from the margins”[xxiv] – disability rights advocates, mental health advocates, suicide prevention advocates, Indigenous groups, religious groups, and advocates for the elderly.[xxv] Canada’s current euthanasia regime represents the preferences of the able-bodied majority.

Bill C-7 essentially introduced a two-track system for obtaining MAiD. In the first track, a patient whose death is “reasonably foreseeable”[xxvi] – a remarkably broad category, as noted earlier – can access MAiD with no waiting period, on the agreement of only one independent witness.[xxvii] The second track allows people who are not dying (in any imminent sense of the word) to access MAiD, such as people with a chronic illness, or paralysis, or other disabilities, subject to a waiting period that may be waived.

John and George Van Popta, brothers and retired pastors, have spoken openly about the risks they see with MAiD being available to people like them. John suffers from Parkinson’s disease, George from multiple sclerosis.[xxviii] Their diseases are chronic and degenerative, but their deaths are not reasonably foreseeable. A common symptom of both of their diseases is depression. While mental illness on its own is not considered to meet the requirements for MAiD, it is an underlying factor that may influence a patient’s desire to live. These men share the concern of many who suffer with chronic illnesses that, if they at a low point ask about MAiD, they will receive suicide assistance, while another person suffering from depression without a chronic illness will be offered all the support and suicide prevention available to able-bodied Canadians.

The law thus creates a value divide between able-bodied Canadians, who are offered suicide prevention, and disabled Canadians, who are offered suicide assistance.[AN3] The law disregards the principle of equal, inherent human dignity. Having abandoned the rule of the inviolability of human life, the government struggles to find a principled basis for distinguishing between those who may or may not be killed when they ask for help to end their life. Consequently, the basis for the distinction is the variable discretionary judgments of a given doctor who considers a person’s quality of life to be sufficiently bad to merit that patient’s request for MAiD.

This legal shift will have cultural impacts. As MAiD becomes more common and acceptable, persons who would qualify for MAiD may begin to feel the need to justify their continued existence. Medical service providers may begin to see those eligible for MAiD who go on living as a drain on resources and a burden to society.[xxix] Indeed, the MAiD-eligible elderly, sick, or disabled may begin to see themselves that way. Such cultural impacts of this legal shift were a major concern of disability rights advocates opposed to Bills C-14 and C-7.[xxx]

Another cultural impact of this legal shift may be the normalization of suicide itself. After all, if assisted suicide is a “dignified” way to die, why not unassisted suicide? A 2015 study indicated that general suicide rates have increased in every American state that has legalized assisted suicide.[xxxi] Liberal MP Robert Falcon Oullette, the lone Liberal MP to vote against Bill C-14, made this point poignantly when tying euthanasia to the Indigenous suicide crisis in Attawapiskat.[xxxii] Others have also expressed concern about the impacts of doctor-assisted suicide on the “suicide pandemic” that haunts Indigenous communities.[xxxiii] Struggling young people who see their grandparents choosing MAiD may feel like suicide is a viable option, supported by their family. Allowing physician-assisted suicide normalizes suicide as an acceptable way to address suffering.[AN4]

MAiD and the copycat effect

Another concern with the expansion of MAiD is copycat or coupling effects when it comes to suicide. The social phenomenon of copycat suicides is well documented. Publicized suicides are often followed by an increase in suicide rates in a given area, completed using disproportionately similar means, especially by persons in a similar demographic as the victim in the publicized suicide.[xxxiv] In light of this, news media follow guidelines on how to report on suicide in a way that minimizes copycat or contagion effects.[xxxv]

No such guidelines exist in relation to MAiD – in fact, the opposite seems to be true. News stories profiling MAiD over the past few years use such terms as “dignified party”, a “celebration of the gift of death”, “[going] out on their own terms,” and as a romantic way for an elderly couple to die together.[xxxvi] Reporting in this style is the norm and, with the wealth of research demonstrating a social contagion aspect to suicide, Canada’s “steady year-over-year growth” in MAiD deaths should come as no surprise.[xxxvii]

Research also shows that suicide is often coupled to a certain place, environment, or event – such that if a given setting is not present, suicide will not take place.[xxxviii] Consider the data from Britain in the 1960s and 70s. In 1963, renowned author Sylvia Plath put her head in her oven to inhale enough coal gas to kill herself through carbon monoxide poisoning. Coal gas was common in British homes in the 1960s, and 44% of suicides in Britain in 1963 involved carbon monoxide poisoning. When the country switched over to natural gas in the 1970s – natural gas has considerably lower concentrations of carbon monoxide – the suicide rate fell dramatically.[xxxix] Suicide was “coupled” with easy access to coal gas. Easy access to MAiD is expected to have a similar effect.

Although MAiD advocates are keen to separate MAiD and suicide, MAiD normalizes, even glamourizes, suicide. People struggling with the frailty of old age or with permanent disability may see MAiD as a clean and easy way to end their lives. Reporting MAiD stories in a positive light induces others to consider MAiD. Will doctor-assisted suicide, now widely available, become for persons with a disability or chronic illness the coal gas of 1960s Britain? Will we see assisted suicide rates – and suicide rates in general – continue to climb?

Canada should support suicide prevention for everyone at any stage of life. Anything else requires value judgements about the worth of another’s life – judgments that no human being should be making. The Supreme Court fallaciously argued there are only two options when facing suffering: end your own life early or suffer until you die.[xl] But as many experts have been arguing for years, physical and psychological suffering can be effectively relieved through palliative medicine and appropriate counselling.

Expanding euthanasia in Canada

Since the decriminalization of euthanasia and assisted suicide in 2015, more than 20,000 medically assisted deaths have been recorded in Canada.[xli] Nearly all (99%) were euthanasia deaths, in which a physician or nurse practitioner directly administered lethal drugs (as opposed to assisted suicide, where the patient self-administers the drugs provided to them).[xlii]

The vast majority (84.9%) of Canadians requesting MAiD cited the loss of their ability to engage in meaningful activities as their reason for choosing MAiD, while more than a third (35.9%) cited feeling like a burden to loved ones.[xliii] People typically have several reasons for seeking MAiD, the most predominant of which are relational – based not on physical pain, but on existential, spiritual, social, or psychological suffering.

Before 2015, assisting in suicide and consensual homicide were serious criminal offences in Canada.[xliv] Parliament’s response to the Supreme Court’s Carter decision allows for medical professionals to intentionally kill their patients in exceptional circumstances without criminal sanction (see sections 241(2) – 241.4 of the Criminal Code). However, MAiD remains homicide – “causing the death of a human being” – under the Criminal Code.[xlv] The legal question in every situation where MAiD is administered is whether the homicide is culpable or not culpable.[xlvi] This is a legal, not merely a medical, question.

Outside the setting of a physician/patient relationship, it is no defence to a charge of murder or manslaughter that the deceased consented to his own death.[xlvii] Counseling someone to commit suicide remains a crime in all circumstances,[xlviii] but aiding suicide remains a crime only outside the MAiD context. And it is hard to prove that a doctor who informed his patient about MAiD did not in effect counsel the patient to choose, or at least to consider, MAiD. Patients look to their physicians for advice and guidance about the best treatment option for them. Giving a professional recommendation to a patient to consider MAiD and counseling a patient to consider suicide are ethically indistinguishable, and legally nearly impossible to differentiate.

This legal ambiguity contributes to the overall lack of accountability for those who euthanize patients. The sole independent witness affirming a MAiD request can be a nurse or community volunteer with no relation to the patient. Further, the witness only has to be present for the request for assisted suicide, not for the actual procedure itself (see s. 241.2(3)(c)). Thus, the “safeguards” of ensuring the patient has “an opportunity to withdraw their request” and “gives express consent … immediately before providing the medical assistance in dying” (section 241.2(3)(d) and (h)) are toothless – no other person needs be in the room at the time the lethal dose is administered![xlix] Furthermore, which track to follow (the “fast track” of s. 241.2(3) where natural death is foreseeable or the “slow track” of s. 241.2(3.1) where natural death is not foreseeable) is left to the whim of the euthanizing doctor, as the legislation states that a prognosis as to the specific length of time the patient has remaining does not need to be made.[l]

Once MAiD has been administered, there is little legal recourse if someone believes a doctor acted inappropriately[AS5] .[li] Concerned family members who have asked the police to investigate have been referred to the Ministry of Health. Police seem to want to avoid getting involved in this politically charged issue. Besides, where could we expect the police to begin an investigation with a dead victim and few (if any) witnesses, all of whom approved the death?[lii]

We are all vulnerable

Some Canadians have been pressured into choosing MAiD. One family was horrified to learn that their mother, Joan, had consented to be euthanized after being presented with the option while in the hospital, alone, in a heavily medicated state. Only after the family advocated for her and brought her home for palliative care was Joan able to say, “Absolutely not. I want to live.”[liii]

Dr. Margaret Somerville, founding director of the Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law at McGill University, says the Supreme Court of Canada’s notion that suicide is freely chosen so long as the person is competent and not subject to coercion represents an extremely myopic understanding of human vulnerability.[liv] Social, psychological, and emotional factors are at play in every end-of-life decision, as we saw in the data detailing why people choose MAiD.

Canada has moved swiftly from discussing euthanasia for terminally ill, near-death patients who request it, as in the Carter case, to proactively offering it as an option to those with any serious illness or disability. There are those who think we have not gone far enough, who think euthanasia should be an option for people with advanced dementia who can no longer confirm their consent,[lv] or for teenagers with cancer,[lvi] paralysis, or depression, or even for babies with severe birth defects, at their parents’ request.[lvii] Opening the door to MAiD transforms our conception of suicide from “a tragedy we should seek to prevent to a release from suffering we should seek to assist.”[lviii]

The legal availability of MAiD shifts the societal discussion from how to alleviate suffering to which sufferers can be eliminated. [AS6] It demonstrates a profound lack of compassion toward the most vulnerable Canadians: the elderly, the sick, the chronically depressed, those with disabilities, and the lonely. Even if a person has the requisite “grievous medical condition,” her desire to die may be the result of a complex web of factors including hopelessness, fear, loneliness, shame, conflict with family members, emotional abuse, lack of access to palliative care, and so on.[lix] Canada has supposedly introduced euthanasia to grant people greater autonomy in controlling their end-of-life experience, but this comes at the expense of loving, life-affirming care.

Every life is inherently worthy of protection by law, regardless of physical or mental limitations.[lx] The sanctity of human life is the foundation for human rights and equality under the law.[lxi] If individual autonomy trumps the sanctity of life, the most dependent among us are at risk.[lxii] Legalizing assisted suicide does not enhance the autonomy of suffering individuals. The change in the Criminal Code is to protect the euthanizers, not the patient. The legal change only provides a new criminal defence for some people (physicians) to take the lives of people in a particular class (suffering adults). The decision over who qualifies is made by state actors, not by ‘autonomous individuals.’[lxiii]

Improve Canada’s MAiD framework

Following the Carter (2015)and Truchon (2019)decisions, the government created exceptions to longstanding criminal prohibitions on homicide and aiding suicide. These are fundamental shifts in our law that are easily abused with fatal consequences for Canada’s most vulnerable.

An ongoing exploration of whether and how to expand euthanasia in Canada is unnecessary. Parliament is not required to broaden access to euthanasia (or indeed, even to permit euthanasia at all[lxiv]). Considering evidence of cultural shifts and abuses from other jurisdictions, Parliamentarians should be studying issues related to the vagueness and permissiveness of the current law. Is it being consistently interpreted? Are physicians following the law, or only the self-made guidelines of stakeholder groups? Is everything possible being done to manage patient suffering in ways other than bringing about their deaths? Is there enough accountability and oversight to ensure the current law is being properly enforced? What changes can be made to improve monitoring and enforcement of safeguards for the most vulnerable?

It is a right goal of government to protect vulnerable Canadians: those with disabilities, illnesses, and advanced age. Our current law places vulnerable people at risk and fails to affirm the intrinsic worth of all human beings. The civil government has no job more important than to maintain and enforce laws that equally protect the lives of all. [AS7] The Supreme Court of Canada has stated that “the state’s execution of even one innocent person is one too many.”[lxv] We agree. The trial judge in the Carter case noted that “none of the [other legalized] systems has achieved perfection.”[lxvi] Canada is no different. When MAiD is legal, innocent people will die.

Policy recommendations

ARPA Canada respectfully calls on Parliament to do everything in its power to uphold the intrinsic worth of all human life. The government crossed a sacred line by passing legislation permitting euthanasia. It ought not to continue expanding access to this extreme measure. Parliament should amend Canada’s current permissive law to better protect those most vulnerable to abuses.

Recommendation #1: Eradicate ableism – The only way to ensure that MAiD is not an ableist program (discriminating against people on the basis of disability) is to decouple it from disability and reserve it as an option that is strictly limited to those who are suffering at the very end of their lives. Parliament can do so by:

- amending the eligibility criteria in section 241.2(2) by adding “(d) a medical practitioner with expertise in the condition that is causing the person’s suffering provides a written opinion that the person’s prognosis is six months or less” and

- deleting subsection 241.2(3.1) (safeguards for persons whose death is not foreseeable).

Failing that, “reasonable foreseeability of death” must be clarified to address the appalling abuse of the term and the “fast tracking” of patients with years left to live.

Recommendation #2: Increase waiting periods

- Amend section 241.2(3) to reinstate a minimum 10-day waiting period for all MAiD requests.

- For those whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable, subsections 241.2(3.1)(g) and (h) require other options to be discussed and consultations with service providers offered. Patients with “fast track” cases should have a right to benefit from those services as well. Therefore, s. 241.2(3.1)(g) and (h) should be added to subsection 241.2(3) as well.

- Further, ss. 241.2(3.1)(g) and (h) should be strengthened. It is not enough that a patient has been “offered consultations” with other professionals. Their doctor should be required to facilitate meetings with others who may be able to help their patient live well.

- The Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians says the 90-day period (in the “slow track”) is insufficient to find satisfactory ways to manage a person’s symptoms or to help them adjust to an illness or disability.[lxvii] Parliament should amend section 241.2(3.1)(i) to extend the waiting period for those whose death is not reasonably foreseeable to 180 days, or 6 months.

- The 90-day waiting period is ambiguous, given that it begins on the day the doctor begins to assess a patient’s eligibility, not the day a written request for MAiD is signed. A straight-forward amendment would be to add a clarification in subsection 241.2(3.1)(i) that the 90-day waiting period begins the day the patient makes a written, signed, dated, and witnessed request for MAiD.

Recommendation #3: Preclude mental illness – Parliament must preclude mental illness and psychological suffering from MAiD eligibility. Parliament must repeal Clause 6 of Bill C-7 (2021) which will otherwise automatically extend MAiD to people with mental illness as a sole underlying condition as of March 2023.[lxviii] In addition, Parliament should add a paragraph to the end of section 241.2(2) explicitly stating that “(d) a mental illness or psychiatric disorder is not a grievous and irremediable medical condition for the purposes of this section.”

Recommendation #4: Prohibit inducing suicide – The preambles to Bill C-14 (2016) and Bill C-7 (2021) state that their goal is to protect vulnerable people from being “induced” to end their lives. Yet the Criminal Code does little to prevent such inducement. Counseling a person to consider suicide remains a crime in all circumstances. Therefore, counselling or encouraging a person to seek a “medically assisted death” should be prohibited generally, and medical personnel in particular should be prohibited from mentioning or discussing MAiD with a patient unless the patient explicitly asks.[lxix]

Parliament must reinforce the prohibition in section 241(a) – counseling to commit suicide – by clarifying that medical professionals may only provide information about the provision of medical assistance in dying upon request.[lxx] Section 241(5.1) should be amended to state: “For greater certainty, no social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, therapist, medical practitioner, nurse practitioner or other health care professional commits an offence if they provide information to a person on the lawful provision of medical assistance in dying upon the person’s request.”

Recommendation #5: Enhance witness safeguards – Given that the choice for MAiD is easily open to manipulation and abuse, and the outcome final, Parliament must ensure an extremely high standard of informed consent for MAiD.

- Reinstate the two independent witnesses requirement in section 241.2(3)(c) and 241.2(3.1)(c).

- To give meaningful effect to the safeguards in s. 241.2(3)(d) and (h) and s. 241.2(3.1(d), (g), (h), and (k), and s. 241.2(3.2)(b), (c), and (d), (3.3), and (3.4), Parliament must amend those sections to require two independent witnesses to be present when MAiD is performed (not only when a written request is made).

- Furthermore, the final discussion and administration of the lethal substance process ought to be audio-video recorded to allow for judicial scrutiny and verification that all safeguards were followed. Subsections 241.2(3), (3.1), and (3.2) should be amended accordingly in a way that balances privacy concerns with ensuring safeguards for the vulnerable.

Recommendation #6: Require judicial oversight – Require judicial oversight, approval, and review for every MAiD case. Eligibility for assisted suicide and proper safeguards and procedures also involve legal questions, not merely medical questions. Current law only requires two physicians or nurse practitioners to decide that a person may be killed, and people can choose which physicians or nurse practitioners to visit. Since people cannot choose their judge, adding judicial oversight protects against cluster effects based on rogue doctors who interpret the rules liberally or play loose with the safeguards.

Recommendation #7: Increase penalties – Parliament must reinforce that MAiD is a narrow exception to the crime of assisting suicide. Thus, a medical practitioner who violates the rules, safeguards, and procedures of this carefully crafted exception has committed a crime and should be liable to the same criminal liability. Parliament should amend 241.3 to match the penalty for assisting suicide. Repeal 241.3(b) and amend 241.3(a) to read “… is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 14 years.”

Recommendation #8: Eliminate waiver of consent – Section 241.2(3.2) allows for a patient to make a “written arrangement” granting medical practitioners the authority to unilaterally decide – with no second opinion and no witnesses – when a patient has lost capacity to give or withhold consent to medical care and to then kill the patient at that time (provided capacity is lost before a date specified in the written arrangement). Unlike a written request for MAiD, which requires one witness, this subsequent “written arrangement” requires no witness or second medical opinion.[lxxi]

Further, sections 241.2(3.2)(c), (3.3), and (3.4) contemplate that such a patient might possibly demonstrate refusal to be killed after seeming to have lost capacity, but that the practitioner need not give the patient any opportunity to refuse. The preamble to Bill C-7 noted the “inherent risks and complexity” of allowing people to waive contemporaneous consent to being killed, yet it established no safeguards or oversight for the use of this mechanism whatsoever. This is an appalling oversight. Parliament should repeal subsections 241.2(3.2), (3.3), and (3.4). In the alternative, Recommendation #5(c) is essential.

Recommendation #9: Prohibit compelled participation in homicide or suicide – Section 241.2(9) states, “For greater certainty, nothing in this section compels an individual to provide or assist in providing medical assistance in dying.” To provide more teeth to section 241.2(9) and to protect conscience rights and the integrity of the medical profession, Parliament should add a further clarifying section: 241.2(9.1) “For greater certainty, any person who compels an individual to provide or assist in providing medical assistance in dying is guilty of (a) an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 5 years; or (b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.”

Endnotes

[i] Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), [2015] 1 SCR 331, 2015 SCC 5.

[ii] Bill C-14, (42-1) Statutes of Canada, June 17, 2016.

[iii] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), sections 241(2) – 241.4.

[iv] Carter v. Canada, supra note 1, at para. 56 and 127.

[v] ARPA Canada, Protecting Life: How Parliament Can Fully Ban Assisted Suicide Without Section 33, September 2015, at p. 4.

[vi] Truchon v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 QCCS 3792.

[vii] The term “Medical Aid in Dying” or “MAiD” is an intentionally misleading euphemism and confuses genuinely ethical aid in dying like palliative care with a form of homicide (physician-assisted suicide and/or euthanasia). We object to the euphemism and only refer to it in this report due to the prevalence of the term in medicine, law, and public discourse.

[viii] Dr. Madeline Li, expert witness in the Lamb case in the B.C. Supreme Court (Lamb v. Canada (Attorney General), 2017 BCSC 1802) developed and oversees the MAiD program at the University Health Network in Toronto. She notes in her expert report that psychological suffering is the main reason for assisted dying requests in all jurisdictions where it is legal (para. 6 on p. 5). Dr. Li describes the case of a woman who had bone cancer and a history of chronic depression (see paras. 20-21). This patient was assessed by two “experienced MAiD providers” (not by her oncologist or psychiatrist) who approved her for MAiD. After her 10-day waiting period, she changed her mind and decided to pursue a palliative approach. Later, during another medical crisis, she requested MAiD again. Her MAiD physician decided that there were no concerns about her apparent ambivalence. But two days before her planned MAiD intervention, she changed her mind again and agreed to undertake new cancer therapies. This illustrates, Dr. Li says, the difficulty of accounting for the influence of anxiety or depression and other factors in a patient’s request for MAiD. It also demonstrates the importance of waiting periods, and of offering all possible supports to a patient. Air Canada and other airlines give you 24 hours to cancel your flight penalty-free. Bill C-7, however, would permit a person to request MAiD and be euthanized the same day or hour. It is not at all clear why the government thought deleting this safeguard was necessary.

[ix] Dr. Wiebe, who has euthanized several hundred people, says she goes by a roughly 10-year prognosis – a very loose standard from a scientific and medical perspective. See Joan Bryden, “Experts Concerned Ottawa has revived uncertainty over meaning of foreseeable death in assisted dying bill,” Globe and Mail, (March 3, 2020).

[x] Section 241.2(2.1) of the Criminal Code states, “For the purposes of paragraph (2)(a), a mental illness is not considered to be an illness, disease or disability.” However, Bill C-7, which received royal assent on March 17, 2021, includes clause 6 which will come into force on March 17, 2023. Clause 6 will automatically repeal section 241.2(2.1) unless Parliament passes an Act to the contrary before that date.

[xi] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), sections 241.2(3)(c).

[xii] Para. 883, as cited in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 SCC 5 at paras. 27 and 105.

[xiii] See Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012 BCSC 886 at paras. 649-671.

[xiv] Text taken from the headnote summary of Fleming v. Ireland & Ors, [2013] I.E.H.C. 2 (H.C.), summarizing paras. 88-105 of the judgement. Judgement unanimously upheld on appeal to the Supreme Court of Ireland.

[xv] Bringing Up Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) as a clinical care option. (2020) Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers.

[xvi] The Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers has published multiple resources for MAiD providers, including one on reasonable foreseeability of death, stating that death doesn’t have to be foreseeable in any set time frame, only reasonably predictable based on illness or age trajectory.

[xvii] Advice given verbally by presenters at the annual CAMAP conference, attended in both 2019 and 2021.

[xviii] Favaro, A., St. Philip, E., and Slaughter, G. Family says B.C. man with history of depression wasn’t fit for assisted death. CTV News, Sept 2019.

[xix] Government of Canada, Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada, 2020.

[xxi] Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17.

[xxii] Greek Medicine, “The Hippocratic Oath”.

[xxiii] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), section 241(1)(a).

[xxiv] “Voices from the Margins” is a term used by the Vulnerable Persons Standard, which promotes five evidence-based safeguards to protect the lives of vulnerable Canadians in a society where MAiD is legal.

[xxv] A review of the submissions made to the Parliamentary committees studying Bills C-14 and C-7 show a clear majority of disability groups and their allies urging restraint.

[xxvi] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s. 241.2 (2)(d).

[xxvii] Bill C-7 applies a one-witness requirement whether one’s natural death is reasonably foreseeable or not – meaning the issue is not the time it takes to find two witnesses. The value of two witnesses is that if anything suspicious emerges about the circumstances of a patient’s MAiD request or death, the account of two witnesses can be compared. A person needs two witnesses to create a last will and testament. Surely it is not too much to ask to have two witnesses sign a request to have a medical practitioner euthanize someone. Bill C-7 also lowers the bar for who qualifies as an independent witness. It allows medical practitioners or others who are paid to provide health care or personal care, including someone who provides care to the person who is requesting MAiD. The danger here is that medical personnel or support workers who approve of and grow accustomed to MAiD, or who work for a MAiD provider, may be routinely relied on to be the sole witnesses.

[xxviii] John and George Vanpopta, MAiD changes deny suicide prevention help. The Hamilton Spectator, March2021; John Van Popta and George Van Popta also shared their stories on video for ARPA Canada – those are available via YouTube.

[xxix] Charles Lewis, “The burden of mercy,” The National Post, 30 November 2007. See also Factum of the Council of Canadians with Disabilities in the Carter Case at the Supreme Court of Canada, particularly paras. 26-38.

[xxx] Council of Canadians with Disabilities’ Disability-Rights Organizations’ Public Statement on the Urgent Need to Rethink Bill C-7, The Proposed Amendment to Canada’s Medical Aid in Dying Legislation.

[xxxi] David Albert Jones and Dr. David Paton, “How Does Legalization of Physician-Assisted Suicide Affect Rates of Suicide,” Southern Medical Journal 108 (10): 599-604.

[xxxii] Parliament of Canada: Edited Hansard 046; 42nd Parliament, 1st session, May 2, 2016. MP Oulette states, “In the indigenous tradition and philosophy, we are required to think seven generations into the future. If I am wrong and there is no connection between Attawapiskat and physician-assisted dying or suicide, if the average person does not see a connection and communities do not see a greater stress, then I will gladly say I was wrong; but if there is an impact, which is caused by the valorization of suicide, then what?”

[xxxiii] Tim Fontaine, “Cree communities launched and funded own inquiry into “suicide pandemic.” CBC News, March 16, 2016.

[xxxiv] See for example Jang, S. A., Sung, J. M., Park, J. Y. & Jeon, W. T. (2016). Copycat suicide induced by entertainment celebrity suicides in South Korea, Psychiatric Investigation, 13 (1), 74-81 and Stack, S. (2003). Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 238-240.

[xxxv] Sinyor, M., Schaffer, A., Heisel, M.J., Picard, A., Adamson, G., Cheung, C.P., Katz, L., Jetly, R., & Sareen, J. (2017) Media Guidelines for Reporting on Suicide: 2017 Update of the Canadian Psychiatric Association Policy Paper.

[xxxvi] Tara Bowie, “B.C. man chooses death with dignified party – music, whisky and cigars included.” The Abbotsford News, March 6, 2019; Catherine Porter, “At his own wake, celebrating life and the gift of death.” New York Times, May 25, 2017; Sara Fraser, “P.E.I couple who used medically assisted dying “went out on their own terms” says family.” CBC News, June 4, 2021; Jonel Aleccia, “This couple died by assisted suicide together. Here’s their story.” Time, March 6, 2018.

[xxxvii] Government of Canada: First Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada, 2019, section 3.1.

[xxxviii] Malcolm Gladwell, Talking to Strangers: What we should know about the people we don’t know. (2019: Little, Brown and Company, New York), pp. 265-296.

[xxxix] Kreitman, N. (1976) The Coal Gas Story. United Kingdom Suicide Rates, 1960-71. British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine, 30 (2), 86-93.

[xl] The fallacy is most obvious in the Supreme Court’s opening paragraph in the Carter decision (emphasis added), “It is a crime in Canada to assist another person in ending her own life. As a result, people who are grievously and irremediably ill cannot seek a physician’s assistance in dying and may be condemned to a life of severe and intolerable suffering. A person facing this prospect has two options: she can take her own life prematurely, often by violent or dangerous means, or she can suffer until she dies from natural causes. The choice is cruel.”

[xli] Government of Canada, Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada, 2020.

[xlii] Ibid, section 3.1.

[xliii] Ibid, section 4.3.

[xliv] In the 2015 Carter v. Canada (Attorney General) decision, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the absolute prohibition on assisted suicide in s. 241 of the Criminal Code and on consenting to homicide in s. 14.

[xlv] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), section 222(1) states, “A person commits homicide when, directly or indirectly, by any means, he causes the death of a human being.”

[xlvi] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), s. 222(1)-(5). See also s.227, which states at (1): “No medical practitioner or nurse practitioner commits culpable homicide if they provide a person with medical assistance in dying in accordance with section 241.2.” Note the word “if”, which distinguishes between culpable and non-culpable homicide.

[xlvii] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), s. 14: “No person is entitled to consent to have death inflicted on them, and such consent does not affect the criminal responsibility of any person who inflicts death on the person who gave consent.”

[xlviii] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), s.241(1)(a), which states, “Everyone is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 14 years who, whether suicide ensues or not, (a) counsels a person to die by suicide or abets a person in dying by suicide”. This section has no exemptions in the provisions for MAiD and remains absolutely prohibited.

[xlix] The potential for abuse here is overwhelming. See, for example, the story of serial killer nurse Elizabeth Wettlaufer who murdered at least 8 patients in long-term care homes, a fact which came to light only because she came forward and confessed to the crimes, before MAiD was even legalized. The province launched the Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System under the oversight of Court of Appeal Justice Eileen Gillese. How can we be sure that similar things don’t happen with other patients if doctors who end the lives of their patients are allowed to be alone with them in the room at the time of lethal injection?

[l] Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46), s.241.2(3), which states, “before a medical practitioner or nurse practitioner provides medical assistance in dying to a person whose natural death is reasonably foreseeable, taking into account all of their medical circumstances, without a prognosis necessarily having been made as to the specific length of time that they have remaining, the medical practitioner or nurse practitioner must…[list of safeguards].”

[li] ARPA Canada, Protecting Life, supra note 5, at p.8. See also Schutten, André, “Lethal Discrimination: A Case Against Legalizing Assisted Suicide in Canada,” The Supreme Court Law Review (2016) 73 S.C.L.R. (2d), 143-184, esp. p. 168-179.

[lii] Favaro, A., St. Philip, E., and Slaughter, G. Family says B.C. man with history of depression wasn’t fit for assisted death. CTV News, Sept 2019.

[liii] O’Neill, T. Elderly cancer patient was pushed toward euthanasia, family says. BC Catholic, June 28, 2021.

[liv] Margaret Somerville, “What the top court left out in judgment on assisted suicide,” The Globe and Mail, Published 27 October 2015, Updated 15 May 2018.

[lv] Elizabeth Raymer, “Advance directives “crucial” missing element in medical assistance in dying laws: senator.” Canadian Lawyer, June 10, 2021.

[lvi] David Amies, “Dr. David Amies: Is it right to forbid mature minors access to assisted dying?” Dying with Dignity Canada, July 5, 2019.

[lvii] Dr. Derrick Smith, as quoted in Andrew Coyne, “Canada is making suicide a public service. Have we lost our way as a society?” National Post, February 29, 2016; see also Fabienne Tercaefs, “Mother asks for medical assistance in dying for minors.” ici.radio-canada.ca, Aug. 12, 2021.

[lviii] Andrew Coyne, “Canada is making suicide a public service. Have we lost our way as a Society?” National Post, 29 February 2016.

[lix] Vulnerable Persons Standard, “Introducing the Vulnerable Persons Standard.”

[lx] A fuller explanation of this is available in ARPA Canada’s factum in the Carter case before the Supreme Court of Canada,

[lxi] ARPA Canada, Protecting Life, supra note 5, at p. 5.

[lxii] ARPA Canada has published a book on this topic – Building on Sand: Human Dignity in Canadian Law and Society, by Mark Penninga.

[lxiii] André M. Schutten, “Lethal Discrimination: A Case Against Legalizing Assisted Suicide in Canada.” Supreme Court Law Review (2016) 73 S.C.L.R. (2d), 143-184, at p. 156.

[lxiv] ARPA Canada has published a special report explaining how prohibiting euthanasia and assisted suicide is a constitutionally valid option: Protecting Life: How Parliament can fully ban assisted suicide without section 33. The report includes draft legislation.

[lxv] United States of America v. Burns, [2001] 1 S.C.R. 283, 2001 SCC 7, at para. 102; see also paras. 70-71, 76-78.

[lxvi] Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2012 BCSC 886, at para 685.

[lxvii] Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians Submission to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights on Bill C-7: An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (medical assistance in dying]. October 30, 2020.

[lxviii] Section 241.2(2.1) of the Criminal Code states, “For the purposes of paragraph (2)(a), a mental illness is not considered to be an illness, disease or disability.” However, Bill C-7, which received royal assent on March 17, 2021, includes clause 6 which will come into force on March 17, 2023. Clause 6 will automatically repeal section 241.2(2.1) unless Parliament passes an Act to the contrary before that date.

[lxix] Consider the sad story of Roger Foley, 42, an Ontario man suffering from an incurable neurological disease. The hospital staff offered him medically assisted death, despite his repeated requests to live at home, “Chronically ill man releases audio of hospital staff offering assisted death,” CTV News, 2 August 2018.

[lxx] The problem of patients being offered MAiD without asking for it was noted in an official UN Report. In the “End of Mission Statement” (April 12, 2019) of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the Rapporteur writes:

I am extremely concerned about the implementation of the legislation on medical assistance in dying from a disability perspective… I have further received worrisome claims about persons with disabilities in institutions being pressured to seek medical assistance in dying, and practitioners not formally reporting cases involving persons with disabilities. I urge the federal government to investigate these complaints and put into place adequate safeguards […].

[lxxi] To be clear, there is no requirement for any witnesses or second medical opinion:

1. when the “written arrangement” for waiver of final consent is formed;

2. when the practitioner decides to warn the patient of “risk of losing capacity” (241.2(3.2)(a)(iii));

3. when the practitioner decides the patient has lost capacity (241.2(3.2)(b)); or

4. when the practitioner kills the patient.