Canada’s drug crisis: a wicked public policy problem (Part 1)

“If ever by some unlucky chance such a crevice of time should yawn in the solid substance of their distractions, there is always soma, delicious soma, half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon.”[1]

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, the drug soma makes the populace happy and complacent. The government of this dystopia provides it to the people and teaches them to depend on it. If any pain or distress arises, citizens simply need to take soma to escape from the difficulties of reality.

But our society is not so approving of drug dependency. So how do so many become addicted? Why do some stay addicted while others succeed in quitting? What will help solve the problem of drug addiction? There are no easy answers. In this series, I start by reviewing the nature of the drug crisis in Canada and the factors that contribute to it. In the next two articles, we will look at how biblical principles can help inform our response to the problem. The final article of the series will suggest some possible solutions.

The nature of the drug crisis

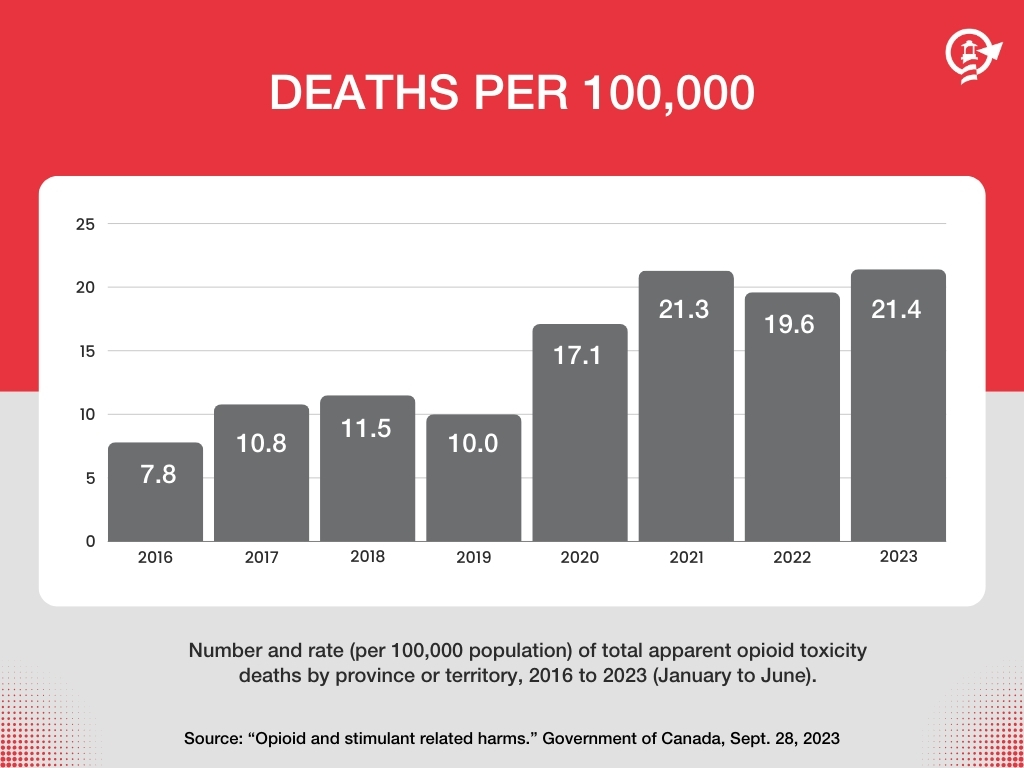

Between January 2016 and June 2023, over 40,000 Canadians died from drug use. Over the first six months of 2023, 89% of drug deaths happened in BC, Alberta, and Ontario (these three provinces make up only 64% of the Canadian population). 84% of opioid deaths involved fentanyl, and 80% involved non-pharmaceutical opioids.[2] In 2016, Canada averaged 7.8 deaths per 100,000 people from drug use, and that increased to 21.2 deaths per 100,000 by mid-2023.[3]

British Columbia has the highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the country. Drug deaths per 100,000 people per year in the province increased from 20.1 in 2019 to 48.3 in June 2023.[4] Alberta has the second highest rate, at 41.4 per 100,000 in June 2023.[5] Of the remaining provinces, overdose deaths per 100,000 are high in Saskatchewan and Ontario and relatively low in Quebec and Eastern Canada.[6]

Factors contributing to the drug crisis

Drug addiction in Canada exploded after OxyContin was introduced as a prescription painkiller in the 1990s. OxyContin was marketed as a non-addictive drug and readily prescribed to many patients. But it was highly addictive.[7] Overuse and misuse of prescription drugs increases the likelihood of illegal drug use and addiction, and this is what happened with OxyContin and other prescription drugs.[8] A significant amount of drug use stemmed from improper use of opioids (painkillers). While painkillers are necessary at times, they should not always be considered the first line of treatment and caution must be used to avoid addiction. The Christian Medical and Dental Association (CMDA) notes in a position statement that, “Christian healthcare professionals who know the unique hope Christ offers to suffering humanity should be alert to signs that a patient’s request for opioid medication for pain may signify or be part of a deeper need.”[9]

Another major factor in the increase of overdose deaths was the introduction of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 30-50 times stronger than heroin. Just two milligrams of fentanyl is enough to kill a person.[10] It’s potency in small quantities makes it easier to smuggle and cheaper to distribute, but also more deadly.[11] In 2012, fentanyl was associated with just 4% of drug overdose deaths. This number rose to 87% in 2018.[12] Often, drug users will think they are buying heroin or another drug, when in reality they are buying fentanyl or a drug laced with fentanyl.

Cheap prices also worsen the drug crisis. Prices have fallen along with increased supply and relatively easy access to drugs.[13] For example, in Vancouver, morphine used to cost $20 per tablet. Now, the same amount costs $1.[14] In London, Ontario, prices for 8 milligrams of hydromorphone have decreased from $20 just a few years ago to $2 in 2023.[15]

The cost, availability, and potency of opioids are all factors in the ongoing drug crisis. But we also live in a society that is increasingly turning away from God. Francis Schaeffer explains that gradually in the 1900s the Christian foundations of Western society were removed, and life became largely meaningless. Schaeffer writes, “because the only hope of meaning had been placed in the area of nonreason, drugs were brought into the picture.”[16] Drug use became preferable to the meaninglessness of everyday life and the hope that was ultimately placed in material goods.

Many turn to drugs to escape the challenges of life, to dull pain, loneliness, or fear. Or a spirit of hedonism takes over, aiming to live for pleasure in the present with little regard for the future. Such people may start taking drugs occasionally but this occasional use, especially at younger ages when the brain is still developing, often grows into a dependence on drugs.

At the same time, our society is becoming more fragmented and isolated. According to a 2019 Angus Reid Survey, nearly half of Canadians were isolated, lonely, or both. Those least likely to be isolated or lonely are those who are married and have children and those who take part in faith-based activities.[17] As churches, families, and other institutions break down, social isolation grows. Social isolation is also linked to the development and exacerbation of opioid addiction.[18] The social isolation experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, intensified problems with drug addiction.[19]

Responses to the Problem

Throughout the country, possession of hard drugs is illegal. However, provinces can apply for exemptions under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. For example, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Quebec have all received exemptions for various supervised consumption sites in their provinces. British Columbia has received an exemption from criminalizing possession of small amounts of drugs, and the City of Toronto has applied for a similar exemption. Officially, most drugs remain illegal under federal law.

Nevertheless, provinces respond to drug use and abuse in different ways. There are three overarching approaches that governments have used to combat the drug crisis.

Incarceration

Traditionally, the war on drugs meant that both drug dealers and users were subject to jail time, although drug use and possession were often only prosecuted when combined with other criminal offences. A wide range of substances are currently illegal under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which clarifies offences and what the punishment should be. Recently, the federal government removed mandatory minimum penalties for several drug-related offences, giving more leeway to judges and more opportunity to apply alternative sentences.

Safe Supply and Harm Reduction

The major political parties have largely moved away from promoting jail time for minor drug offences. Increasingly, the dominant policy approach favours publicly funded access to drugs with the goal of harm reduction. Harm reduction, that is, trying to avoid overdose and death from drug use instead of punishing or discouraging drug use, is the buzzword in most drug policy circles today.

Last year, the province of BC decriminalized possession of up to 2.5 grams of hard drugs after the federal government granted them an exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[20] BC has also focused on providing so-called ‘safe supply.’ Safe supply “refers to providing prescribed medications as a safer alternative to the toxic illegal drug supply to people who are at high risk of overdose.”[21] The reason these drugs are called ‘safe’ or ‘safer’ is because the drug content is known and will be less likely to cause overdose. The drugs prescribed, however, are still powerful substances. Proponents of safe supply argue that it will not only reduce overdoses and deaths, but that it will also reduce crime because addicts will not have to steal to get enough money for drugs. Some believe it will allow drug users to manage their addiction and live normal lives.[22]

Canada’s first safe injection site opened in Vancouver in 2003.[23] The federal government began investing in safe supply programs, publicly funding the supply of addictive drugs, in 2020.[24] So the approach of British Columbia towards drugs is not entirely new. However, it is more focused and comprehensive than previous attempts.

The goal of the BC government in decriminalizing drugs is to “reduce the stigma and isolation that prevents people from reaching out for help and leads to people using alone.”[25] Yet the BC government also attempt to pass legislation to restrict the use of drugs in public spaces following concerns about drug use in communities, particularly near areas where kids play.[26] This law was stopped by a court injunction (in effect until the end of March) stating that this restriction would cause “irreparable harm” to drug users.[27]

Recovery-Focused Approach

The primary alternative drug policy approach in Canada is now commonly deemed ‘the Alberta model.’ It focuses on improving treatment and recovery options for drug addicts while continuing to prosecute both trafficking and possession of hard drugs. As the Alberta government states, “a recovery-oriented system of care is a coordinated network of personalized, community-based services for people at risk of or experiencing addiction and mental health challenges.” They note that such an approach requires a shift in philosophy, looking at drug abuse and recovery holistically.

Alberta still has safe consumption sites, where addicts can access drugs for the purpose of avoiding withdrawal symptoms as they work towards recovery. However, the province tracks data and information about usage and uses the safe consumption sites as a means to encourage addicts to enter treatment and recovery. Addicts must take the drugs at the clinic where they receive them, and the clinic will work with the addict to try to help them recover. Alberta is also increasing access to treatment beds and has eliminated the fee previously required for treatment beds. They have also created a Narcotic Transition Program which allows drug addicts to start treatment on powerful opioids to avoid withdrawal, and slowly reduce the amount they consume.[28]

Elements of treatment and recovery are not new to provincial responses to drug abuse, but Alberta’s approach is more focused than previous attempts. The Alberta model is “based on the belief that recovery is possible, and everyone should be supported and face as few barriers as possible in their pursuit of recovery.”[29] The Alberta model has been a significant focus of that government since 2023, although elements of it began in 2019.[30]

A complex policy issue

There are many aspects to drug policy including the psychology and treatment of addiction, the costs and benefits of criminalizing hard drugs, the societal impacts of drug addiction, the need to protect the lives of addicts while also dissuading the public from drug use, the extent to which the government should be involved in the first place, and so on. Similarly, there are many potential ways of addressing problems of drug trafficking, drug experimentation and addiction, and rising overdose deaths.

Canada’s drug crisis is one which might be called, in public policy, a ‘wicked problem.’ Wicked problems are hard to define and even harder to solve. A large part of the challenge is also the conflicting values and interests between adherents of the various perspectives on the issue. For example, when discussing drug policy, liberals might believe that drug use is a health problem, and that the solution is for the government to simply aim to reduce bodily harm. Libertarians might view this issue through the lens of freedom and autonomy and think that the government has no authority over what substances people put into their bodies or how they recover. People on the conservative side of the political spectrum may consider drug use to be a moral issue with the proper response being the criminalization of drug use and trafficking. All three of these underlying perspectives – health, freedom, and morality – are important, but how can we balance these three perspectives?

Stay tuned for more articles in this series, in which I hope to break this wicked problem down further and discuss how biblical principles help inform an effective public policy response to Canada’s drug crisis, how the image of God informs public policy, how moral agency factors in, and what role the government should play in responding to drug use and abuse.

[1] Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1946) 62.

[2] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada,” Government of Canada, December 2023.

[3] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[4] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[5] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023. See also “Alberta substance use surveillance system,” Government of Alberta, Dec. 2023.

[6] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[7] “The US drug abuse epidemic is killing 300 Americans a day,” Al Jazeera, The Bottom Line, June 8, 2023.

[8] “Misuse of Prescription Drugs Research Report: Overview,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, June 2020. See also “Prescription Opioids and Heroin Research Report: Introduction,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, Jan. 2018.

[9] “Opioids and Treatment of Pain,” Christian Medical and Dental Association, April 21, 2020.

[10] Benjamin Perrin, Overdose (Toronto, Canada: Penguin Random House, 2020), 17.

[11] Perrin, Overdose, 60.

[12] Perrin, Overdose, 13.

[13] Line Editor, “Q & A, Part 2: ‘Our fatal overdose numbers have gone down dramatically off the peak’”, The Line, Jan. 13, 2023.

[14] Line Editor, “Q & A, Part 2: ‘Our fatal overdose numbers have gone down dramatically off the peak’”, The Line, Jan. 13, 2023.

[15] Adam Zivo, “The Liberal government’s safer supply is fuelling a new opioid crisis,” National Post, May 9, 2023.

[16] Francis Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2021): 235.

[17] “A Portrait of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Canada today,” Angus Reid Institute, June 17, 2019.

[18] Nina C. Christie, “The role of social isolation in opioid addiction,” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 16(7) (July 2021): 645-656.

[19] Alexiss Jeffers et al., “Impact of Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health, Substance Use, and Homelessness: Qualitative Interviews with Behavioral Health Providers,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(19) (Oct. 2022). See also Aganeta Enns et al., “Evidence-informed policy brief – Substance use and related harms in the context of COVID-19: a conceptual model,” Public Health Agency of Canada, Sept. 16, 2020.

[20] Michelle Ghoussoub, “B.C. will decriminalize up to 2.5 grams of hard drugs. Drug users say that threshold won’t decriminalize them,” CBC News, June 3, 2022.

[21] “Safer supply,” Government of Canada, April 25, 2023.

[22] Perrin, Overdose, 170.

[23] Vancouver’s supervised injection site, the first in North America, opened 13 years ago. What’s changed? | National Post

[24] Future of Canada’s first-ever ‘safer supply’ drug program uncertain with funding set to end in spring | CBC News

[25] “B.C. takes critical step to address public use of illegal drugs,” BC Gov News, Oct. 5, 2023.

[26] “B.C. takes critical step to address public use of illegal drugs,” BC Gov News, Oct. 5, 2023.

[27] Tristin Hopper, “Why B.C. ruled that doing drugs in playgrounds is Constitutionally protected,” National Post, Jan. 2, 2024.

[28] Adam Zivo, “The UCP’s victory in Alberta is a win for Canadian addiction policy,” National Post, June 3, 2023.

[29] “The Alberta Model: A Recovery-Oriented System of Care,” Government of Alberta, 2023.

[30] “The Alberta Model: A Recovery-Oriented System of Care,” Government of Alberta, 2023.