How Well Are We Fulfilling God’s Original Command?

When God created the world, he gave man a foundational command commonly known as the cultural mandate: “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion” over it (Genesis 1:28). There are five imperatives in this cultural mandate, but the first three – be fruitful, multiply, and fill the earth – all have to do with reproduction. It is striking that the very first three commands given by God to His image-bearers have to do with having children.

So how well are we as humanity in general, as Canadians, and as Christians fulfilling this command?

Well, not very well.

How well are we fulfilling God’s original command?

Although Christians and demographers might have some debate on when or if the earth is “full,” it is difficult to argue that Canada is “full.” Canada has one of the lowest population densities of any country on the planet, with an average of only 4 people per square kilometre. By comparison, the Netherlands, one of the most densely populated countries (so excluding islands and city-states) has a population density 130 times that of Canada, or 518 people per square kilometre. Although much of Canada’s landmass is not suitable for human habitation, Canada still has the third most arable land per person in the world, with 1.04 hectares (0.0104 square kilometres) per person. That’s 17 times as much farmland per person as the Netherlands (0.06 hectares per person).

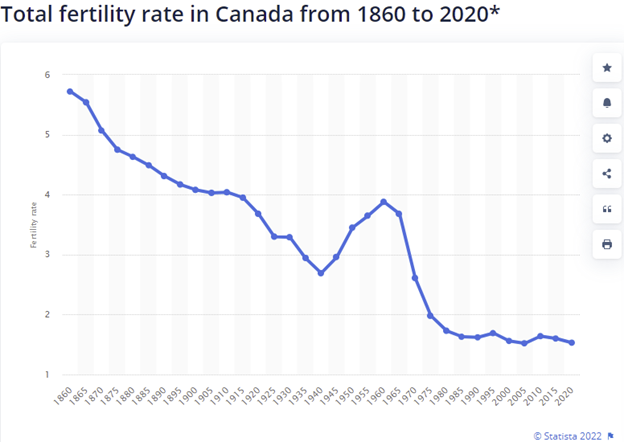

Relating to the command to be fruitful and multiply, Statistics Canada recently published some of the results of the latest census, focusing on the changing demographics of Canada. (Statistics Canada oversees a census of the entire population every five years; the latest census was in 2021.) Among its findings, it reports that the total fertility rate – the number of children that a woman can be expected to have in her lifetime – has been declining for decades. In 2020, the last year for which the birth rate is available in Canada, the birth rate hit an all-time low of 1.40.

What does this statistic mean? Well, the fertility replacement rate is 2.1, meaning that if the average woman in Canada had 2.1 children, Canada’s population would remain the same. This makes intuitive sense. Each woman would have to have two children to replace herself and her husband. Since not every woman lives long enough or is able to have children, the natural replacement rate is a little bit higher than two. If fertility rates exceed 2.1, Canada’s population would grow, but if fertility rates are below 2.1, the Canadian-born population will decline.

With the current fertility rate of 1.40, the Canadian-born population is guaranteed to decrease in the long term as more Canadians will die each year than will be born.

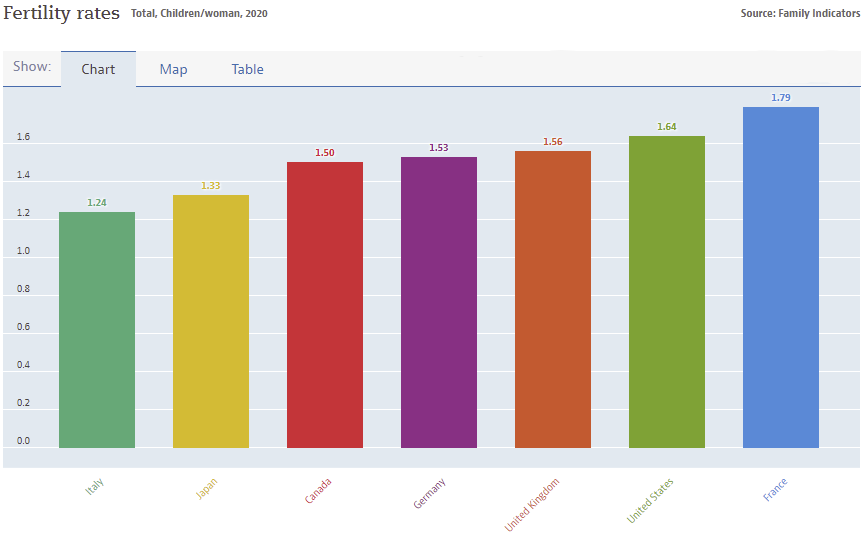

This trend is not unique. The fertility rates across the G7 (a group of Canada’s comparable wealthy and democratic peers) are all below the replacement rate of 2.1 according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Why Aren’t We Fulfilling this Command?

Fertility rates have been falling across the developed world for a number of reasons. The Institute of Marriage and Family, which joined the Christian think tank Cardus in 2016, identified three main reasons in a past report on Canada’s Shrinking Families.

First of all, economic factors are incentivizing smaller families. Raising children is becoming increasingly expensive, with the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada estimating that raising a child under the age of 18 costs $10,000-$15,000 in direct costs each year, plus the opportunity costs of lost wages. Given that the median after-tax income of Canadian families was $66,800 in 2020, children take up a substantial portion of a family’s budget. Women have also increasingly decided to pursue a full-time or part-time career rather than being homemakers. These changing preferences have led many women to decide not to have children or to have a smaller number of kids than their parents or grandparents did.

Secondly, Canadian families are becoming less stable, prompting fewer couples to decide to have children. Cardus’ Canadian Marriage Map demonstrates how, of the total number of families with children, the percentage of married couples has declined while the percentage of common-law couples and lone-parent families has increased. As of 2016, approximately one-third of families with children lack a married couple at the helm. Almost half of all couples – common-law and married – do not have children.

Thirdly, the prevalence of contraception and abortion has enabled Canadians to choose when to have children and how many children to have. Contraceptive pills, approved in Canada in 1960, as well as other forms of contraception have become widely used. When contraception fails, many Canadians turn to abortion. Although the number of documented abortions has been declining over the past decades (74,155 abortions were reported in 2020), there is little data on the number of abortion pill prescriptions, which have become increasingly common in recent years.

What are the consequences of not fulfilling this command?

The major consequence of a low fertility rate is an aging and possibly declining population. Statistics Canada’s 2021 census report documents how the Baby Boomer generation (the uncommonly large age cohort born in the decades after the Second World War) is retiring from the workforce. In 2016, the number of people over the age of 65, the age traditionally associated with retirement, exceeded the number of people under the age of 15 for the first time in Canada. Five years later, approximately one-fifth of the Canadian population (19.0%) is over the age of 65 while 16.3% of the population is below the age of 15. This trend is projected to continue, as the number of retirees grows faster than the number of children in the foreseeable future. The number of people in the labour force compared to the number of retirees is also declining, meaning that there are increasingly fewer workers paying taxes to support our retirees each year.

The economic impact of an aging population is significant. In 2006, the Senate of Canada released a report on demographics forebodingly entitled The Demographic Time Bomb: Mitigating the Effects of Demographic Change in Canada, documenting how transfers to seniors and the health care costs of seniors would eat up an increasing percentage of government spending. This is a major consideration of whether federal or provincial finances are sustainable in the long term (over the next 75 years). According to the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s 2021 Fiscal Sustainability Report, the federal government’s finances and public pension plans are sustainable over the long-term but provincial/territorial finances are not sustainable, due primarily to “rising health care costs due to population ageing.” When the federal government, provincial/territorial government, and public pension plans are considered together, their fiscal policy is not sustainable over the long term, again, largely because of the aging of the population.

How might we better fulfill this command?

One way to reverse this demographic decline and at least fill our corner of the earth is through immigration. And that is precisely what Canada has done. Despite having a fertility rate well below the replacement rate (meaning that Canada’s population should shrink in the long-term) Canada’s population continues to grow, primarily through immigration. In 2021, Canada welcomed more immigrants than any other year in its history – 401,000 – and the federal government has stated its intentions to keep immigration rates high. While the populations of other G7 countries declined (Japan and Italy) or grew slowly (Germany, France, United States, and the United Kingdom) in the past five years, Canada’s population grew relatively quickly at over 1% per year.

While immigration may help mitigate our aging demographics and help Canadians collectively fill their country, God’s command to be fruitful and multiply applies to individuals too. Canadians simply aren’t having many children. Even Pope Francis recently pointed out this issue, arguing that too many people are choosing to have pets instead of children.

Changing the cultural conversation about children isn’t primarily the task of the government. Given the economic, cultural, and technological factors that are encouraging Canadians to have fewer kids, the ultimate fix isn’t a governmental policy but a renewed understanding of and appreciation for the goodness of children. Children are not primarily a financial burden, a drag on career aspirations, or an unwelcome source of work, but a joy and a heritage from the LORD (e.g. Psalm 127:3-5).

Nevertheless, government policies certainly can help ease some of these factors. Cash transfers to parents such as the Canada Child Benefit and generous parental leave policies alleviate some of the economic costs of children. Reforming Canada’s laws on marriage and divorce could help support stable marriages that are conducive to having children. Restricting abortion, both surgical abortions in hospitals and clinics and abortion pills taken at home, would increase the fertility rate as well.

Conclusion

Canada as a country, with a fertility rate of 1.40, is not fulfilling God’s command to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth” well. Economic factors, cultural attitudes towards marriage, contraception, and abortion are all pressuring or enabling Canadians to have fewer and fewer children. Canada’s low fertility rate is leading to the rapid aging of our society, a trend that is only partially offset by increased immigration. Although changing cultural attitudes towards children is better led by the Church rather than the government, government policies can certainly also be reformed to encourage citizens to be fruitful and multiply.