New Policy Report: Spanking

Update: Click here for an EasyMail letter that lets you contact your MP about this bill quickly and personally.

Our latest issue of Respectfully Submitted is on its way to all MPs and Senators and tackles the sensitive subject of corporal discipline, more commonly referred to as spanking. We strongly encourage you to give it a read (click on attachment below for the clean PDF) and ask your MP what they thought of it. Our donors will be receiving a copy in the mail soon and others will be able to pick up a copy at future ARPA events.

Respectfully Submitted – Corporal Discipline – April 2013

Since 1997, Members of Parliament have introduced no fewer than eight private member’s bills to fully ban corporal punishment, also known as physical discipline, smacking, or spanking. Currently, Bill S-214, introduced by Senator Céline Hervieux-Payette, awaits second reading in the Senate. Her previous effort in 2008 passed through the Senate but died when an election was called. And it’s not just Parliamentarians. A 2012 editorial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal make the same case: “It is time for Canada to remove this anachronistic excuse for poor parenting from the statute book.”

Since 1997, Members of Parliament have introduced no fewer than eight private member’s bills to fully ban corporal punishment, also known as physical discipline, smacking, or spanking. Currently, Bill S-214, introduced by Senator Céline Hervieux-Payette, awaits second reading in the Senate. Her previous effort in 2008 passed through the Senate but died when an election was called. And it’s not just Parliamentarians. A 2012 editorial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal make the same case: “It is time for Canada to remove this anachronistic excuse for poor parenting from the statute book.”

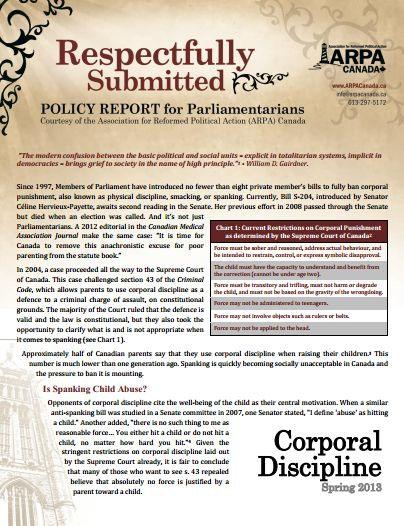

In 2004, a case proceeded all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. This case challenged section 43 of the Criminal Code, which allows parents to use corporal discipline as a defence to a criminal charge of assault, on constitutional grounds. The majority of the Court ruled that the defence is valid and the law is constitutional, but they also took the opportunity to clarify what is and is not appropriate when it comes to spanking (see Chart 1).

Approximately half of Canadian parents say that they use corporal discipline when raising their children.[3] This number is much lower than one generation ago. Spanking is quickly becoming socially unacceptable in Canada and the pressure to ban it is mounting.

Is Spanking Child Abuse?

|

Chart 1: Current Restrictions on Corporal Punishment as determined by the Supreme Court of Canada[2] |

|

Force must be sober and reasoned, address actual behaviour, and be intended to restrain, control, or express symbolic disapproval. |

|

The child must have the capacity to understand and benefit from the correction (cannot be under age two). |

|

Force must be transitory and trifling, must not harm or degrade the child, and must not be based on the gravity of the wrongdoing. |

|

Force may not be administered to teenagers. |

|

Force may not involve objects such as rulers or belts. |

|

Force may not be applied to the head. |

Opponents of corporal discipline cite the well-being of the child as their central motivation. When a similar anti-spanking bill was studied in a Senate committee in 2007, one Senator stated, “I define ‘abuse’ as hitting a child.” Another added, “there is no such thing to me as reasonable force… You either hit a child or do not hit a child, no matter how hard you hit.”[4] Given the stringent restrictions on corporal discipline laid out by the Supreme Court already, it is fair to conclude that many of those who want to see s. 43 repealed believe that absolutely no force is justified by a parent toward a child.

|

“I have looked at just about every study I can lay my hands on, and there are thousands, and I have not found any evidence that an occasional mild smack with an open hand on the clothed behind or the leg or hand is harmful or instills violence in kids” – Dr. Jane Millichamp |

There are, of course, other activities involving force, activities well beyond the scope of parental discipline. For example, martial arts involve controlled physical force with a goal of enhancing the child’s well-being (providing protection, strength, self-control and dexterity). A child enrolled in martial arts will be subject to force, pain, and physical discipline. There is potential for the force to cross the line and become abuse; yet it is socially and legally accepted that the physical nature of the instruction is not in itself harmful or abusive. If physical force in all of its forms is abuse (as those opposed to corporal discipline argue), then Parliament should be willing to tackle all martial arts, football, rugby, and even hockey!

Examining the Research

“Adults who were subjected to physical punishment such as spanking as children are more likely to experience mental disorders.” [5] These were the opening words of a 2012 CBC story, one of dozens like it, in response to a study that was published in the journal Pediatrics. It isn’t hard to find news reports and articles that pronounce the disastrous effects of spanking. Yet a closer look at the actual research reveals an important detail that many leave out. The Pediatrics journal article looked at the effects of “harsh physical punishment (i.e., pushing, grabbing, shoving, slapping, hitting)”[6] which is different than the conditional spanking that Canada’s Criminal Code allows. Yet the media applied these findings to spanking, with very little context. This is symptomatic of the vast majority of public discourse on this controversial subject. Just as self-defence training is not the same as assault, not all physical discipline is the same. The research must differentiate between different methods of physical discipline.

|

Chart 2: Common Errors in Corporal Punishment Research |

|

Physical discipline is not compared with alternative discipline methods; |

|

Severe physical discipline is not distinguished from non-abusive physical discipline |

|

Correlation between physical discipline and aggressive behaviour is often inferred as causation. |

In 2007, researchers conducted the first ever scientific review of studies that compared physical discipline with alternative methods. Twenty-six studies from the past fifty years were examined and the conclusion was not all that revolutionary: “Whether physical punishment compared favorably or unfavorably with other tactics depended on the type of physical punishment.” The study also looked at what they called an “optimal” type of physical discipline – conditional spanking. As reflected in the parameters laid out by our Supreme Court (see Chart 1 above), conditional spanking is non-abusive, done sparingly, and under control. “Conditional spanking was more strongly associated with reductions in noncompliance or antisocial behavior than 10 of 13 alternate disciplinary tactics.”[7] In other words, when physical discipline is administered in keeping with Canadian law, it came out as good as, or better than, all other forms of discipline studied.

With a 1-2-3-4 punch, the review findings also challenged the oft-argued response that the only positive outcomes of physical discipline are short-term compliance:

- 1)“The effect sizes of conditional spanking compared favorably with alternative tactics for all disruptive behavior problems, including antisocial behavior and defiance.”

- 2)“Physical punishment competed just as well with alternative tactics for long-term outcomes as for short-term outcomes.”

- 3)“[A]ll types of physical punishment were associated with lower rates of antisocial behavior than were alternative disciplinary tactics.”

- 4)“[T]his meta-analysis failed to detect negative side effects unique to physical punishment.”[8]

These findings are consistent with a 2006 New Zealand study, the first long-term study in the world that separated individuals who were spanked with an open hand from those who were never spanked or those who were inflicted with severe physical punishment. It tracked 962 children, born in 1972 and 1973, until they were 32 years old. Jane Millichamp, the lead author, noted, “Study members in the ‘smacking only’ category of punishment appeared to be particularly high-functioning and achieving members of society.”[9] She also concluded that they found no evidence that parents who spanked their children progressed to abusive punishment. One finding that surprised the researchers was that “non-physical punishment was most frequently regarded as the worst punishment ever received, with 50% of [study members] naming at least one non-physical punishment method such as privilege loss.”[10]

Sweden’s Smackdown

|

Chart 3: Findings from Dr. Larzelere’s Review of Sweden’s Smacking Ban[11] |

|

Changes in attitude about corporal discipline occurred before the 1979 legislation, but very little since then. |

|

Physical child abuse by relatives against children under seven increased 489% from 1981-1994. |

|

519% increase in criminal assaults by children under age 15 (born after law), against children age 7-14. Compare with the 231% increase by 15 – 19-year-olds (who were 0-4 when law passed), 133% by 20 – 24-year-olds and only 53% increase by 25 – 29-year-olds. |

|

A shocking 46-60% of cases investigated under Sweden’s law result in children being removed from homes. 22,000 Swedish children were removed from homes in 1981, compared to 1,900 in Germany, 710 in Denmark, 552 in Finland, and 163 in Norway. |

In 1979, Sweden became the first nation in the world to outlaw all physical discipline. This approach is often heralded as an example that all other civilized countries should follow. University of Manitoba professor Joan Durrant has been a leader on this front, thanks to her report, A Generation without Smacking, which argues that Sweden’s model has been a huge success by changing attitudes about corporal punishment, reducing child abuse, reducing violence by children, and allowing professionals to intervene before violence escalates. Sadly, much of her research has been accepted without question, because most of her sources were written in Swedish. That was the case, until Dr. Robert E Larzelere reviewed her findings and found most of them to be completely out of sync with the data on which she based her findings (see Chart 3).

Anti-spanking advocates are also quick to claim that any sanctions for spanking would be civil, not criminal. Parents would be taught proper parenting rather than thrown in jail. But does Sweden’s example bear this out? Consider the 2010 case of a mother and father from Karlstad, Sweden who were jailed for nine months each and were ordered to pay 25,000 kronor ($11,000) to each of their three children who were spanked. More damaging than the jail and fines, all four of their children were removed from their home. Although the court concluded that the parents “had a loving and caring relationship to their children” apparently spanking is serious enough to merit such a sentence.[12] Legislators have to ask themselves whether a child is better off with their loving parents who may occasionally administer physical discipline or with someone else, after having been forcefully removed from their parents, with a chasm of distrust and fear created by the State.

As a side note, New Zealand followed Sweden’s example and adopted anti-spanking legislation. In 2009, just two years later, a whopping 88% of voters in a public referendum asked that the law be rescinded.[13]

The Underlying Issue: The State as Parent

Senator Hervieux-Payette argues, “Parents do not own their children. Children are individuals. Their protection should therefore take precedence over the protection of adults and over the imaginary risk of legal action against them.”[14] If we were to apply this argument consistently, the implications on children would be devastating. Children are not intellectually capable of understanding the depraved world around them, nor capable of exercising their own rights. Someone must do so on their behalf. Senator Hervieux-Payette, along with many bureaucrats and legislators, would like that decision-maker to be the State.

|

“This triangle of truisms, of father, mother and child, cannot be destroyed; it can only destroy those civilizations which disregard it.” – G. K Chesterton

|

State parenting is increasingly being pushed in Canadian public policy. Anti-bullying legislation and mandatory classes in secularism are two recent examples of the State imposing its worldview on children, often in violation of the will of the parents. Even if we hold to a naïve worldview that assumes the best of humanity, history should teach us that when the State has this power, children are sacrificed to political ideologies. Contrast this with the family unit, in which parents as the decision-makers love their children and would sacrifice their own lives for them. The State is not capable of loving its citizens. Not only do parents have an emotional and spiritual connection to their children that the State lacks, they also (usually) have a biological connection. Thankfully, reproductive technologies have not advanced to the degree where the State can father children.

Canada is built on the foundation of liberty. The role of the State is limited to preserving an orderly society and punishing wrongdoers (including actual child abusers), so that the other institutions of society can go about their respective tasks and flourish. The institution of the family has its own governance that is independent of the State and accountable directly to God. A State that becomes father or mother or attempts to usurp their role is a State that views itself as god. Those who balk at mixing religion and politics would have every reason to fear this Statist religion. Even a secular and pluralist Canada should tremble at the prospect of such an Orwellian authority.

Recommendation

Parliament must uphold section 43 in Canada’s Criminal Code, allowing for conditional physical discipline for those parents who choose it as an appropriate form of correction for their child. Parliament must also respect the jurisdiction of the other institutions that govern in society, especially the jurisdiction of families.

Respectfully submitted,

The Association for Reformed Political Action (ARPA) Canada

We welcome your feedback, concerns, and requests for research. Email [email protected] or call 1-866-691-2772.

—————————————-

[1]Gairdner, William D, The War Against the Family: A Parent Speaks Out on the Political, Economic, and Social Policies That Threaten Us All. Toronto: Stoddart Publishing Co. 1992, p 4.

[2] Barnett, Larua, “The “Spanking” Law: Section 43 of the Criminal Code,” Parliament of Canada, online: <http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/LOP/ResearchPublications/prb0510-e.htm>.

[3] Fletcher, John, “Positive parenting, not physical punishment,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, (4 September 2012) Volume 184 No. 12. Online: <http://www.cmaj.ca/content/184/12/1339>.

[4] Mrozek, Andrea, and Dave Quist, “Spanking is Not Child Abuse,” Ottawa Citizen, (25 June 2007) Online: http://www.imfcanada.org/news/spanking-not-child-abuse.

[5] CBC News, “Spanking may be linked to later mental disorders,” July 2, 2012 Online: < http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/story/2012/06/29/spanking-mental-health-drug-abuse.html>.

[6] Afifi, Tracy, Natalie P Mota, Patricia Dasiewicz, Harriet L MacMillan, and Jitender Sareen “Physical Punishment and Mental Disorders: Results From a Nationally Representative US Sample,” Pediatrics, (2 July 2012). Available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2012/06/27/peds.2011-294.7

[7]Larzalere, Robert E and Brett R Kuhn, “Comparing Child Outcomes of Physical Punishment and Alternative Disciplinary Tactics: A Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, Volume 8, No. 1, (March 2005) at p. 26.

[8]Larzalere, “Comparing Child Outcomes of Physical Punishment and Alternative Disciplinary Tactics: A Meta-Analysis.” at p. 27.

[9] Collins, Simon. “Smacking study hits at claims of harm,” New Zealand Herald, October 7, 2006. Online: <http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10404809>.

[10] Millichamp, Jane, Judy Martin, John Langley, “On the receiving end: young adults describe their parents’ use of physical punishment and other disciplinary measures during childhood,” Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association, Vol 119 No 1228 (27 January 2006) Online: <http://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal/119-1228/1818/>.

[11]Larzalere, Robert E, “Sweden’s Smacking Ban: More Harm Than Good,” Families First, 2004. Online: <http://www.christian.org.uk/pdfpublications/sweden_smacking.pdf>.

[12] The Local, “Swedish parents jailed for ‘spanking’ kids,” November 27, 2010, Online: <http://www.thelocal.se/30466/20101127/#.UTkHOhzU58E>.

[13] United Press International, “New Zealanders reject spanking ban” August 21, 2009. Online: <http://www.upi.com/Top_News/2009/08/21/New-Zealanders-reject-spanking-ban/UPI-19711250910124/>.

[14] Hervieux-Payette, Céline. “Debates of the Senate,” Third Session, 40th Parliament, Volume 147, Issue 37, (10 June 2010) online: <http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Chamber /403/Debates/037db_2010-06-10-e.htm?Language=e&Parl=40&Ses=3#65>.