Twenty Years of Same-Sex Marriage in Canada

July 20, 2025, marks the 20th anniversary of the legalization of same-sex marriage in Canada. How did we get here? How prevalent is same-sex marriage today? What are the prospects for a return to a traditional definition of marriage? And how might the definition of marriage change in the next twenty years?

In the Beginning

In the beginning, God had a design for marriage. Right after creating man and woman, God instituted the first social institution: marriage. God created humanity male and female, then made it clear that it was not good for man to be alone; man needed a helper, and woman was created from man. “Therefore,” Genesis 2:23 records, “a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh.”

Although the fall into sin led to all sorts of sexual temptations and sins (examples of which are littered throughout Scripture), Jesus re-affirms the institution of marriage as being between one man and one woman for life. Just as “what God has joined together, let not man separate” (Matthew 19:6), so also what God has instituted, let not man redefine.

God knew the fall into sin would lead to humanity trying to redefine God’s created norms. That’s why God explicitly outlaws same-sex activity in the Mosaic law (Leviticus 20:13). Paul describes same-sex activity as a “dishonorable passion” (Romans 1:26-27) and includes homosexuality in two of his lists of sins in his letters (1 Corinthians 6:9 and 1 Timothy 1:10). Both Jews and Christians have upheld the biblical definition of marriage in custom and in law for millennia.

Britain’s Lord Penzance, deciding the legal case Hyde v. Hyde and Woodmansee in 1866, clearly articulated the common law definition of marriage: “I conceive that marriage, as understood in Christendom, may for this purpose be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others.” That definition of marriage guided the United Kingdom and Canada into the twenty-first century.

But as western society, and Canada specifically, has cast off the Christian faith and Christian morals, that definition of marriage has been abandoned.

The Path to Legalization

In 2000, Rev. Brent Hawkes of the Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto solemnized a religious marriage for two same-sex couples. Those same-sex couples then demanded that the province of Ontario issue them marriage certificates, despite the fact that same-sex marriages were not recognized by any level of government. When the province refused to grant them marriage certificates, the same-sex couples took the province to court, seeking the legalization of same-sex marriage.

The opening paragraph of the Ontario Court of Appeal’s decision in Halpern v Canada in 2003 set the stage for the central question of the case:

The definition of marriage in Canada, for all of the nation’s 136 years, has been based on the classic formulation of Lord Penzance in Hyde v. Hyde and Woodmansee (1866): “I conceive that marriage, as understood in Christendom, may for this purpose be defined as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others.” The central question in this appeal is whether the exclusion of same-sex couples from this common law definition of marriage breaches ss. 2(a) [the guarantee of freedom of religion] or 15(1) [the guarantee of equality rights] of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (“the Charter”) in a manner that is not justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1 of the Charter.

In its reasoning, the Court found that only recognizing opposite-sex marriages, but not same-sex marriages, was discriminatory and violated the equality rights of same-sex couples. Rather than striking down Canada’s definition of marriage and leaving it to Parliament to enact a new law or definition (as the courts did on the issues of abortion, prostitution, and euthanasia), the Court unilaterally changed the definition of marriage away from the “the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others” to “the voluntary union for life of two persons to the exclusion of all others.”

This ruling legalized same-sex marriage solely in the province of Ontario. The federal government, however, chose not to appeal the decision, effectively stating that it accepted the redefinition of marriage.

With the Ontario Court of Appeal changing the definition of marriage and the federal government showing itself unwilling to defend traditional marriage, similar cases cropped up in most other provinces and territories. Other provincial courts quickly followed Ontario’s lead in legalizing same-sex marriage. British Columbia was next (July 8, 2003), followed by Quebec (March 19, 2004), Yukon (July 14, 2004), Manitoba (September 16, 2004), Nova Scotia (September 24, 2004), Saskatchewan (November 5, 2004), Newfoundland and Labrador (December 21, 2004), and New Brunswick (June 23, 2005).

By mid-2005, only Alberta, Prince Edward Island, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories had not legalized same-sex marriage.

By then, the federal government was willing to step in. After the Supreme Court affirmed in Reference Re Same-Sex Marriage that changing the definition of marriage did indeed fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government and that legalizing same-sex marriage was consistent with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the federal government introduced Bill C-38. That bill redefined marriage as “the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others.”

With the passage of this bill and its royal assent on July 20, 2005, same-sex marriage became legal across Canada, making Canada the fourth country in the world (after the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain) to recognize same-sex marriage. Since then, same-sex marriage has become solidly entrenched in Canada in both practice and in public opinion.

Demographics of Same-Sex Marriage

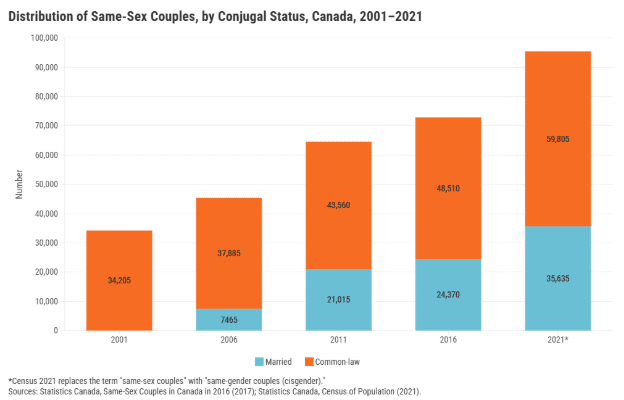

The number of same-sex couples has increased dramatically in the past quarter century. According to the Cardus Marriage Map, which uses data gleaned from the 2021 Canadian Census, there were 95,440 same-sex couples across Canada in 2021. Since 2001 (the first year that data on same-sex unions was collected), the number of same-sex couples has increased by an average of 30% per decade, far outstripping the growth in the number of opposite-sex marriages or growth in the general population.

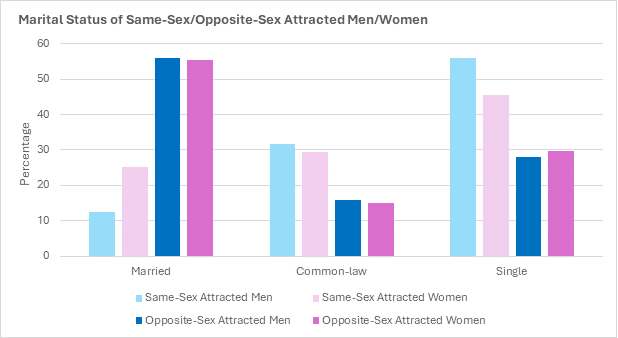

Even with this increase, this chart also shows that men and women who are attracted to members of the same sex don’t all make use of same-sex marriage. While over 50% of heterosexual men and women are married, only 25.3% of same-sex attracted women and 12.5% of same-sex attracted men end up marrying. Nearly twice as many same-sex couples live common law compared to opposite-sex couples. Over 55% of all gay men and 45% of lesbian women are single, compared to just under 30% for men and women who are attracted to the opposite sex.

Political and Public Opinion on Same-Sex Marriage

Political support for same sex marriage changed quickly.

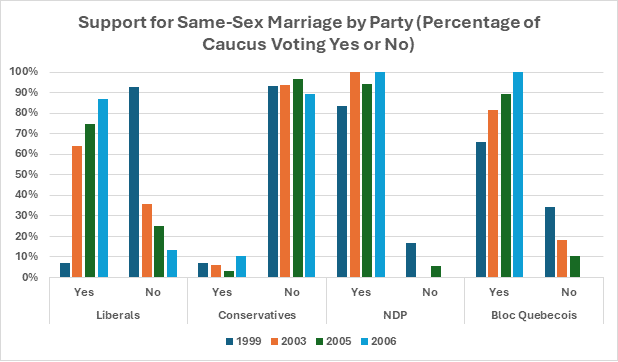

In 1999, there was a motion in Parliament in support of keeping the definition of marriage as “the union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others.” That motion passed by a vote of 216-55. A similar motion was introduced in 2003, with the initial vote ending in a 134-134 tie. In 2005, when the Liberal government introduced its legislation to legalize same-sex marriage, it passed 158-133. After the Conservatives won a minority government in 2006, they introduced a motion to return to a traditional definition of marriage. It was defeated 123-175. No vote on the definition of marriage has been held since.

Table 1: Number of MPs in favour (yes) and opposed (no) to legalizing same-sex marriage

| Liberals | Conservatives | NDP | Bloc Quebecois | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 1999 | 10 | 132 | 5 | 67 | 15 | 3 | 25 | 13 |

| 2003 | 96 | 54 | 5 | 75 | 12 | 0 | 22 | 5 |

| 2005 | 95 | 32 | 3 | 93 | 17 | 1 | 43 | 5 |

| 2006 | 85 | 13 | 13 | 110 | 29 | 0 | 47 | 0 |

The first time Parliament voted on retaining the traditional definition of marriage, there were MPs in every party – Conservative, Liberal, NDP, and Bloc Quebecois – that opposed redefining marriage, though each had a clear majority position on the issue. Over the next few votes, the Conservatives continued to overwhelmingly oppose the recognition of same-sex marriage while the NDP were nearly unanimous in their support of it. However, a greater and greater proportion of Liberal and Bloc Quebecois MPs supported same-sex marriage with every vote. In 1999, only 7% of Liberal MPs voted to redefine marriage. Just four years later, 64% of Liberal MPs voted this way. If a vote were taken now, it’s highly unlikely any Liberal (much less any NDP or Bloc MP) would oppose same-sex marriage.

Even the Conservative Party has abandoned the defence of traditional marriage. While almost 90% of the Conservative caucus opposed same-sex marriage in the latest vote in 2006, the party removed its pro-traditional marriage stance from its Policy Declaration at its 2016 Convention, by a vote of 1,036-462. At the time, prominent Conservative MP Michelle Rempel Garner lauded the decision, saying “I think our party got a little more Canadian today. It’s a milestone and it’s not just a milestone for our party, it’s a milestone for all Canadians. Yes, it took us 10 years to get to this point, but I think this is something that is a beacon for people around the world who are looking at equality rights. Canada is a place where we celebrate equality.”

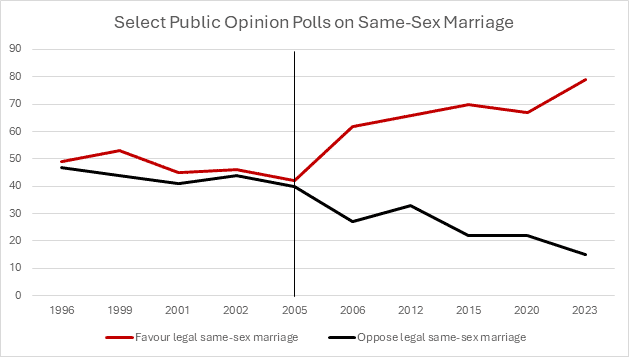

The change in public opinion has been similarly stark. In the decade leading up to 2005, public opinion on same-sex marriage was evenly split. After legalization, support for same-sex marriage surged, standing at about 80% in 2023. Canada now widely celebrates same-sex relationships through publicly funded “Pride” events, changes to school curricula, and many other ways.

The abrupt change demonstrates how powerful the law can be in shaping public opinion. While in many ways politics is downstream from culture, this is a clear example of culture being downstream from politics. In a democracy, only politicians who generally follow the cultural weathervane get elected. But at the same time, our politicians – and, even more importantly, the law – are guideposts for public morality. The fact that something is illegal creates a negative stigma or public opinion around it for many people, regardless of how well that opinion fits into their worldview. Legalize something and remove the stigma and public opinion changes, often drastically.

Public opinion changed drastically on same-sex marriage after its legal recognition, but the same dynamic has also occurred with abortion and euthanasia. In a society that is rapidly abandoning the Christian religion and the moral precepts attached to it, people are looking elsewhere for a moral compass. In many cases, they latch on to the law for moral direction.

Further decline

The societal recognition of marriage as “the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others” has crumbled. Canada undermined the “for life” component of this definition when it legalized no-fault divorce in 1986. The recognition that marriage is between “one man and one woman” was removed through the legal redefinition of marriage in 2005. These changes were possible because marriage has been untethered from its moral foundation in Christianity.

Once untethered, there is no reason – aside from the fact that public opinion isn’t quite there yet – why the definition of marriage cannot drift further away. Without its foundation in God’s institution of marriage, why leave “to the exclusion of all others” in the definition of marriage? Why not legalize polyamory as well and simply define marriage as the “union of [any number of] persons?” There is little public opinion polling around polygamy, but a 2018 poll found that 36% of Canadians favour decriminalizing polygamy (i.e. not making it a crime to have multiple spouses) and 25% favour legalizing polygamy (i.e. Having the government legally recognize polygamous marriages).

The judicial precedents for legalizing polygamy are already starting. In 2016, Ontario’s All Families Are Equal Act allowed up to four people to be the legal parents of a child. A Quebec court just struck down the limit that a child can have only two parents. If more than two people can be the parents of a child, why couldn’t more than two people be married to each other?

Twenty years removed from the legalization of same-sex marriage in Canada, it seems far more likely that the erosion of God’s creational pattern for marriage will continue than that a traditional definition of marriage will be restored in Canadian law. Reformed Christians should be on guard for what might happen in the next twenty years.

Conclusion

The decline of traditional marriage in our culture testifies to how our society has moved further and further from God and his law. Thankfully, the architect of marriage is God, not man. While our society may twist and pervert love and marriage, God still calls many of His children to a marriage that reflects the relationship between Christ and His Church. Marriage is an opportunity for Christians to model faithfulness, loyalty, sacrificial love, and care for another. The fact that this model of marriage has become countercultural should make it shine all the brighter. Christian marriages can stand out as beacons of light that cause people around us to ask questions, giving us opportunity to talk about our faithful, sacrificial Saviour who has such great love for His Church that nothing – neither good times nor bad, riches nor poverty, sickness nor health – can separate us.