When a medical team seems to have exhausted all treatment options and a terminal diagnosis is given, a physician will too often tell a patient, “I’m sorry, there is nothing more we can do for you.” The doctor then refers the patient to hospice or palliative care, which the patient enters with the mindset that nothing can or will be done for them. But there is much that palliative care can offer to patients living with disability, debilitating illness, or facing the end of life. This care should be available to every Canadian in need of it.

Palliative care is holistic, person-centered care for adults and children facing life-limiting or life-threatening illness. As our population ages and medical treatments improve, more Canadians live longer with life-limiting illnesses, and more die of chronic conditions than from sudden causes like heart attack or accidents.[i] These people could benefit for years from the palliative approach to pain and symptom management.

Palliative care recognizes and respects inherent human dignity. It neither hastens death nor unnaturally prolongs life. It offers physical, emotional, spiritual, and social support to give patients their best possible quality of life despite illness or disability. It also encompasses the health and well-being of caregivers and family members.

Palliative care is team-based and involves a range of services delivered by a range of professionals – physicians, nurses, home care workers, pharmacists, physiotherapists, social workers, pastors, therapists, and volunteers may all have a role in supporting a patient and their family.[ii] Ideally, this support is available from diagnosis of a life-limiting illness through to death, is provided in a variety of settings, and extends into bereavement care for those left behind.

Knowing that medically hastened death (commonly referred to as medical assistance in dying or MAiD[iii]) is rapidly increasing in Canada for those with a life-threatening illness or severe disability,[iv] the need for excellent, accessible palliative care has never been more pressing. As the Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians states, “Canadians now have the right to access medical assistance in dying. We need a similar right to access palliative care.”[v]

Palliative care in Canada

Access to palliative care varies enormously across our country. Federal, provincial, and territorial governments have made palliative care discussions a priority in recent years, but little has moved past discussion or research to action. Funded services vary widely, as each province has the freedom under the Canada Health Act to determine which services should be considered medical necessities and funded accordingly.[vi]

Clinicians continue calling for equitable access and the earlier introduction of palliative principles in patient care. Waiting until the last stage of life to introduce palliative care makes the transition unnecessarily intimidating and overwhelming for patients. This is especially true because many Canadians know little about or have misperceptions about palliative care. Earlier inclusion gives patients the maximum benefit and ensures palliative care is not introduced alongside MAiD as an option for relieving suffering.[vii]

The Canadian Institute for Health Information believes that up to 89% of Canadians who die could benefit from palliative care – this encompasses almost everyone whose death is not sudden or unexpected.[viii] Despite this great need for palliative care, only 30% of Canadians who need it have access to specialized palliative care, and only 15% have access to early palliative care in their community.[ix],[x]

Cancer patients and young seniors are currently the most likely recipients of palliative care in Canada. Palliative care originated in cancer care, so it is understandable that cancer patients have the best access to palliative care. But even with their longer history of palliative integration, the Canadian Cancer Society in Ontario found that 40% of cancer patients still do not receive any palliative assessment in the last year of their lives.[xi],[xii]

Stories from Canadian patients demonstrate that most patients do not know how to access palliative care on their own, and palliative care is generally not offered when they are still undergoing active treatment, even with a doctor referral.[xiii],[xiv] By the time palliative care is introduced, the caregiving team is often dealing with patients in physical pain and emotional distress, and with burnt out caregivers. Many consider palliative care to offer too little, too late, if it is offered at all.[xv] Introducing palliative care alongside a diagnosis, in conjunction with discussing treatment options, is the best way to give patients maximum benefit. This will include time for advance care planning, estate planning, and other logistical supports that palliative care teams offer to patients and their families.

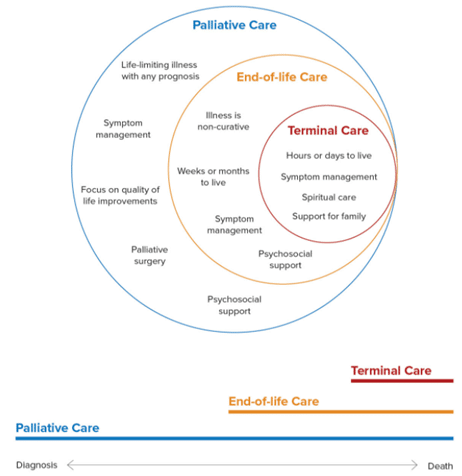

This graphic is helpful in showing the broad scope of palliative care if we do it well.

Image source: https://www.closingthegap.ca/palliative-care-in-ontario-everything-you-need-to-know/

Palliative Care and MAiD

Palliative care has always been centered on giving patients their best possible quality of life through symptom management and holistic personal support. But the expansion of MAiD in Canada is dramatically altering the face of palliative care. Some palliative care facilities and providers now offer MAiD, or are being pressured to do so, blurring the distinction between end-of-life care and simply ending the life of the patient. How can we “reach out with one hand inviting patients to engage in the hard and intense work of addressing their suffering, while in the other hand we hold the needle to end life?” asks Dr. Leonie Herx, a palliative care physician.[xvi]

If someone is facing a life-threatening illness but is given only the options of prolonged suffering or death by MAiD, their consent to MAiD cannot accurately be considered informed consent. Rose[xvii], an 89-year-old woman with congestive heart failure and renal failure following a large heart attack, was sent to hospice for palliative care in anticipation of death. She lived beyond three months in hospice and was well enough to be discharged to residential care. In residential care she complained of ongoing nausea and a sense of having no purpose, feeling useless due to her decline in function. There was apparently no follow-up with palliative care in her new setting and no continuation of anti-nausea medication. She requested and received MAiD for the same suffering which palliative care had so effectively relieved only weeks prior. This tragic tale demonstrates a horrific system-wide failure in a country that prides itself on serving and protecting the vulnerable.

Advocates promote MAiD as an act of compassion for the suffering but, as lawyer Ruth Dick states, “Ironically, with the enactment of the legislation, it is the extent to which we ensure suffering people have robust alternatives to using MAiD that will determine whether Canada is indeed a land of compassion, or one of self-deluded convenience.”[xviii] As of 2018, only 30% of those who received MAiD in a hospital had been identified as having palliative care needs prior to their admission.[xix] Palliative care must be part of the health care conversation and must be made meaningfully accessible to patients long before MAiD is requested or, worse, suggested.

In perspective: Human dignity and suffering

The disconnect that allows some to view palliative care and MAiD as equally valid options in the face of suffering comes from a misunderstanding about the source of life and human dignity. Understanding ARPA Canada’s biblical perspective on this will give context to our recommendation that palliative care be distinctly recognized under the Canada Health Act and that palliative facilities, organizations, and hospices should always maintain the right to be MAiD-free facilities.

Palliative care is generally introduced when a patient faces intense suffering. This suffering can certainly be physical, but also mental, emotional, social, existential, and spiritual. Suffering is unavoidable in this broken world, but we know from the Bible that suffering is not meaningless. While we may not know its purpose in this life, Christians believe that suffering gives us an opportunity to care for others, or to allow others to care for us, and should ultimately point us to God. [xx],[xxi]

In the Book of Job, we read about a man who faced immense loss and suffering and who wrestled with the purpose in that suffering, even asking at one point for the relief of death. But we also hear wisdom as he responds to his wife, who says to him: “Are you still maintaining your integrity? Curse God and die!”He replied, “…Shall we accept good from God, and not trouble?”[xxii] Palliative care is founded on an acceptance of the natural cycle from birth to death, and it recognizes that, though death does not always come easily, life is still to be lived to its natural end.

Each person’s life has a set number of days,[xxiii] and Christians find comfort in the truth that we “are not [our] own but belong, body and soul, both in life and in death, to [our] faithful Saviour Jesus Christ.”[xxiv] We know that nothing – suffering included – can separate us from the love of God.[xxv] The Bible displays a profound recognition of suffering, centered on a God who sent His Son into this world to become man and suffer for us, who wept with us about the ugliness of suffering, and who promises in His time to wipe every tear from our eyes and usher in a world free from pain and suffering. [xxvi],[xxvii] It is our duty and privilege in the meantime to care for fellow human beings in life-affirming, dignity-affirming, personhood-affirming ways.

We do not always get to avoid suffering, but we do get to choose how we face it. Palliative care allows patients to face suffering in community and focuses on maximizing quality of life and maintaining relationships to the end of a person’s natural life. Palliative care’s holistic, person-centered approach to addressing suffering stands in direct contrast to MAiD, which “manages” suffering by simply eliminating the sufferer.

Canadian laws are predicated on the biblical command not to murder.[xxviii] Jesus Christ complements the negative command against murder with the positive command to actively seek our neighbour’s good, to honour and care for them, and to uphold and promote their life.[xxix] Palliative care has at its heart this desire to seek the good of others and to honour and value individuals without exception. MAiD is fundamentally different from palliative care in its open rebellion against God – it seeks to put responsibility for ending life into human hands. MAiD equates killing with caring and as such should have no place in palliative care.

Palliative care is fundamentally different from MAiD in that palliative care recognizes and honors human dignity despite the breakdown of body and mind that leads to dependence on others. Advocates for MAiD focus on the preservation of human dignity as central to a good death, with dignity defined in terms of independence, control, and choice. This advances the idea that human dignity is something that can be lost. But human dignity is inherent: it comes with being created human, and no amount of disease or disability can take that away.[xxx] Palliative care treats all patients with dignity and care, and this treatment aligns with the eternal nature of human souls.

Promoting Compassionate Communities

Pallium Canada, a leader in palliative research and policy in Canada, has developed a “Compassionate Communities”approach to palliative care. Developed by Professor Allan Kellehear in 2011, this social model of palliative care defines a Compassionate Community as one that recognizes that “cycles of sickness and health, birth and death, and love and loss occur every day within the orbits of its institutions and regular activities.”[xxxi] In other words, caregiving, death, and dying are happening all around us and it is our responsibility to accommodate and support those walking through these cycles.

Adequate institutional palliative care capacity should be present in every health region, but home and community care must also be a priority of palliative care funding. Since the 1950s, there has been a shift away from home deaths toward deaths in institutions, and the majority of Canadian deaths now occur in the hospital.[xxxii],[xxxiii] Yet most Canadians, when asked, indicate a desire to die at home.[xxxiv] The Canadian Institute for Health Information finds that those who receive palliative care at home are more likely to avoid emergency hospitalizations and more than twice as likely to be able to die at home.[xxxv] Home care has the added benefit of being more cost-effective than institutionalized care: home care is less than half the cost of hospital care and less than a quarter of the cost of acute emergency care.[xxxvi]

Enhancing home care support ties directly into caregiver support. Palliative care teams aim to support both the patient and their families, and 99% of those who receive palliative care at home have family or friends involved in their care.[xxxvii] Informal caregivers are generally unprepared and unqualified to handle end-of-life care, so support for caregivers is crucial. The Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada recommends that a routine part of all palliative care assessments include not only an assessment of the patient but also an assessment of caregivers’ quality of life, including making them aware of resources to support them.[xxxviii] Excellent online support groups and forums exist, such as Canadian Virtual Hospice,[xxxix] and some local community hospices have volunteers who sit with the dying or their family members, or can link people to a variety of supports such as anticipatory grief support groups. These types of tangible community support for palliative care patients and their families are something provincial and municipal governments can work to expand and improve to reach more communities.

By normalizing the reality of natural death and dying, we also normalize care for those facing this stage of life. A Compassionate Community can be as broad as a town or neighbourhood or as defined as a social group, workplace, faith group, school class, or online group. These communities can provide support in different forms – financial help, social support, prayer, help with meals, paid time off, etc. Integrating palliative care into existing social institutions is the best way to ensure community level support for patients and their families during both illness and bereavement.

Public-private partnerships

Rural and urban settings have different care needs, and even within these contexts each community has unique needs, cultures, and ideas on how to best care for their own members. As our population ages and the need for palliative care rises, we need to get creative if we are to ensure that Canadians with diverse needs all have access to palliative care.

The government can embrace the Canadian value of diversity by supporting independent cultural and religious groups in developing palliative institutions that meet their distinct religious, ethical, or cultural commitments. Public-private partnerships can encourage special interest groups to pursue palliative care options in line with their beliefs, which will ensure that Canadians can access the type of palliative care they desire. While some may argue that these private homes would be too exclusive, in fact they would relieve pressure on the public system, while those who support them also continue to pay taxes which support publicly funded homes.

Provincial governments and local health authorities should partner with cultural and religious groups seeking to offer palliative care services to ensure that proper care standards are met and to maintain an active listing of homes to refer clients to. The federal government could incentivize these groups to start new palliative and hospice facilities by offering a “super tax credit” for donations to charitable palliative care organizations. Limiting this credit to donations made to registered charities ensures that the organizations will be subject to the stringent financial accountability requirements of the Canada Revenue Agency. This approach will allow private groups to maintain autonomy over their palliative care practices, increase contextual palliative care options, and require no direct government funding.

Another way for the government to promote charitable giving to palliative and hospice facilities or home care organizations is a dollar-for-dollar match for donations made by Canadians to registered palliative charities. This would show a government commitment to palliative care as well as issuing a call to Canadians to take up their responsibility as a compassionate national community committed to excellent palliative care.[xl]

Equipping more providers for palliative care

The specialized palliative care workforce is currently not large enough to meet the growing demand for palliative care in an aging population.[xli],[xlii] To provide holistic palliative care to more patients over a longer period than the standard six months or less, other health care providers who are not palliative care specialists need to be able to provide palliative care.[xliii] This is achievable, as more people needing care does not automatically mean they all need the highest level of care. Other providers can apply palliative principles in caring for people with less complex medical needs so that specialized providers can concentrate on those who need the most complex care.

Equipping primary health care providers

Training for all health care providers can improve equitable and timely access to palliative care, especially in smaller health facilities without palliative specialists. Currently, most medical schools dedicate fewer than ten hours throughout all four years of medical school to palliative care training.[xliv] In order to be prepared to meet the needs of an aging population and the accompanying higher rates of chronic illness, medical schools, nursing, and related professional schools need to increase the number of hours spent on training in palliative care and pain and symptom management.

Courses for professional development could also be developed for general practitioners and family physicians. Continuing education for nurses should regularly include palliative topics such as helping patients with advance planning and discerning their treatment wishes. There should also be focused training regarding best ways to address existential symptoms such as loss of autonomy, loss of purpose, and fear of being a burden, which are among the most common symptoms leading to MAiD requests.[xlv]

In a cure-based society, there should be an intentional equipping of medical professionals for palliative care conversations and interventions.[xlvi] Currently, three out of five primary care physicians say they do not feel well prepared to help people needing palliative care.[xlvii] The federal government should establish national standards of training in palliative care, to be met by all Canadian medical schools.[xlviii],[xlix] They should build off work that has been done to develop competency frameworks for various disciplines that have a role in palliative care, from dieticians and psychologists to respiratory therapists and social workers.[l] If we can better prepare health care professionals for conversations about symptom management and death, we will improve palliative support and integration across levels of care.[li]

Paramedics and palliative care

Paramedics are increasingly being called on to manage end-of-life care. Paramedics provide unscheduled emergency care but rarely have practice guidelines or protocols in place to deal with palliative care.[lii] A standard part of educating new paramedics should include training in palliative pain and symptom management and how to communicate effectively with family and caregivers.[liii]

A trial was run in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island that trained paramedics in palliative care, qualifying them to respond to palliative care calls with in-home treatments. This is similar to a program in Alberta, where a first phase report found that 89% of patients were able to be treated at home rather than be hospitalized.[liv] The Maritime study found that families reported improved peace of mind simply by enrolling in the program for access to these specialized paramedics. [lv] Those who made use of the service appreciated the professional and compassionate response of paramedics, and several said emergency department visits would have been necessary without the program. Paramedics who were initially uncertain about the role reported increased confidence in offering palliative care treatments.[lvi]

The 24/7 availability of paramedics makes them an ideal group to support community home care. Their availability and skills are an ideal way to support family caregivers by reducing the mental stress of facing a possible pain crisis without quickly accessible help. This is just one example of how equipping other care providers in symptom management or end-of-life care can make home-based care more feasible by building a support network into communities.

Palliative care for the structurally vulnerable: Bringing care to them

Some of Canada’s most vulnerable die in acute care settings such as hospital emergency rooms or alone outdoors. Poverty, homelessness, addiction, and discrimination all impact access to palliative care when facing a terminal illness. If these vulnerable populations are to receive care, care needs to come to them – home care is not an option if there is no home to be in. Many frontline inner-city workers already engage in holistic end of life care that is similar to a palliative care approach. These workers indicate a lack of formal acknowledgement of their caregiver role and a lack of workplace support, and their voices need to be heard in the palliative care discussion.[lvii]

A program run in Victoria, B.C., in partnership with the University of Victoria, seeks to address some of these difficulties through a mobile palliative care unit. The physician and nurse employed for this project meet clients where they are at – in shelters, low-income housing, or on the street. They create a bridge between vulnerable populations and palliative supports, providing specialized care in a way that makes their clients feel safe and valued. [lviii] These types of innovative programs again recognize the diversity of needs in Canada and seek to meet those needs in creative ways.

Governments and research institutions should work closely with frontline contacts in transitional housing, shelters, inner-city ministries, non-profits, and charities doing community outreach to best understand the local context and needs and to directly reach the vulnerable who are nearing end of life without support. Palliative outreach in these communities can also benefit caregivers, recognizing that caregiver burnout does not only apply to family caregivers, but also to formal caregivers in the wide variety of settings in which they operate.

The holistic approach of palliative care

The World Health Organization says that “palliative care is a crucial part of integrated, people-centered health services” and “a global ethical responsibility.” [lix] Whether the cause of suffering is cancer or major organ failure, severe burns, birth prematurity or extreme frailty of old age, palliative care has incredible value at all levels of care.

Palliative care aims to treat the whole patient – physically, emotionally, spiritually, and socially. It also seeks to support families and caregivers. This holistic nature of care comes with challenges, especially the challenge of effectively coordinating various aspects of care for a single patient. The best models of palliative care have 24/7 availability and a single access point for those receiving care.[lx] This access point allows for ease of access for patients and families as they do not need to remember multiple resources and phone numbers but can communicate directly with one liaison who ensures continuity of care and communication between team members. Shared electronic records, standard assessment tools, and consistent monitoring and measuring of performance all ensure patients receive consistent and high-quality care.[lxi] All regions should fund dedicated palliative care coordinators for this crucial role, as a single access point also makes it easier for referring physicians to know where to send patients regardless of their individual care needs.

Socio-emotional needs and visitation protocols

The goal of palliative care is not to prevent death, but to help people live well to the end of their life. Both physical presence and physical touch are essential parts of that. COVID-19 revealed many structural weaknesses in our health care system and may represent a step backward in the prioritization of holistic patient-centered care. Caught in the wave of targeting preventable deaths, we ignored preventable suffering. The reaction to COVID-19 focused on safety at the expense of meaning and purpose, and many dying people spent their final days, weeks, or months isolated from those they cherished most.

When family members were allowed to visit patients or residents within care facilities, patients were at times beyond the ability to carry on a meaningful conversation, and precious final goodbyes were forever left unsaid. Research shows that final conversations are more valuable in coping with bereavement than actually being present at the time of death,[lxii] so visitor access should always be prioritized in palliative care. Humans are relational, and that element of facilitating relationship is foundational to palliative care as it seeks to meet social and emotional needs alongside physical needs.[lxiii]

Palliative care physician James Downar and his colleague Mike Kekewich point out the increased frequency of delirium and anxiety in patients when visitors are restricted, as well as the poor bereavement outcomes for family members whose social connections and grieving process are disrupted. They note how restrictions reduce the chance of infection but increase the chance of harm from isolation or separation. Their recommendations to counteract these negative impacts include permanent access for visitors during visiting hours and allowing one person to stay with a patient outside of visiting hours.[lxiv]

Promoting physical touch

An important aspect of holistic palliative care is physical touch. Physical touch has been shown to promote sleep, lower blood pressure, and decrease feelings of isolation, anxiety and pain.[lxv] Family members consistently say that hospital beds are a barrier to physical closeness with their loved ones, and so “cuddle beds” are a favourite fundraising project for bereaved loved ones.[lxvi] These extra-large hospital beds allow a loved one to comfortably join the patient in bed, supplying the relational and physical benefits of touch. Training for palliative care nurses should include research on the value of physical touch. They should be taught to encourage physical contact between loved ones – a held hand, a hug, or lying beside them in bed can bring great comfort, but family members may be unsure whether they are free to do this in a formal care setting. Health care funding should also ensure these cuddle beds are available as an option in all palliative care and hospice facilities, just as bariatric beds are available at hospitals for very large patients.

Spiritual care

Part of holistic care is spiritual care for patients and their families. Often as the end of life looms there are questions, fears, or doubts that are beyond what doctors and nurses can address or provide. Existential questions and the comfort of faith and religious practice should be encouraged and engaged. Palliative care facilities should prioritize spiritual leaders as essential visitors, and potentially also employ chaplains or spiritual health practitioners to ensure patients have direct access to spiritual care, regardless of their religious background. [lxvii]

Advance care planning

An important part of palliative care’s holistic approach is helping facilitate difficult conversations and organizing various actions to prepare patients and their families for the end of life. Palliative care aimed at relieving distress includes assistance with things like choosing a funeral home, dealing with financial issues, writing a will, discussing code status options, and clarifying wishes for where and how a person would like to die. Having a plan in place for children, including possibly legacy work like leaving voice recordings or videos or letters for kids or other loved ones, can bring a sense of peace and closure. For those receiving care at home, caregivers are given a detailed treatment and care plan, instructions regarding medication, and told who to call if someone dies at home. Holistic care ensures patients and caregivers know what’s coming and are involved in the planning. Social workers play an important role on a palliative care team in this capacity, and having doctors and nurses equipped for these challenging but crucial conversations can also be of huge benefit to overwhelmed families.

Conclusion

Adopting the ideal, holistic vision of palliative care means prioritizing socio-emotional, spiritual, and mental needs alongside physical needs. It means letting palliative care be what it is meant to be – care – and keeping it distinct from MAiD, which equates killing with care and misunderstands the palliative perspective of inherent human dignity.

Ing Wong-Ward, who was in palliative care as she progressed through colon cancer, expressed how valuable palliative care can be in improving quality of life despite suffering: “I was really surprised by how comforting it was,” she said. “…For so long, we were lurching from one crisis to another. It was like this rollercoaster ride, and suddenly I was in this office with this person who spent an hour listening to what I wanted, what my goals were, where I was at, and she basically indicated that her job was to shepherd me through what is the most difficult period of my life. It was, in the end, really reassuring.”

Moving forward, palliative care should be increasingly a standard part of medical care, introduced in varying degrees alongside diagnosis and engaged throughout treatment as well as through the final weeks and days of life. Together we can increase awareness and understanding around the benefits offered by a palliative care team and can build supportive and compassionate communities across Canada that are prepared to engage in excellent palliative care.

Recommendations

- The federal government should recognize access to palliative care as a separate and distinct right under the Canada Health Act.

- The federal government should develop standardized terminology and measures around palliative care and implement national data collection on palliative care access and delivery to determine if system changes lead to improvement. In conjunction with this, the federal government should pursue national standards of training in palliative care to ensure consistency and quality across the country.

- Provincial governments should work with professional associations and educational institutions to improve palliative care training across the healthcare spectrum so that Canadians have earlier and increased access to palliative care.

- Make palliative care training a mandatory part of paramedic training to increase 24/7 professional palliative care support in all communities.

- Hire palliative care coordinators in all health regions who ensure physicians have up-to-date information about palliative care, and who serve as a single access point for patients and their families.

- Include advance planning and end-of-life conversations as part of all doctor and nurse training to increase provider comfort with death and the surrounding conversations, and so improve palliative support across levels of care.

- Provincial health authorities should require signed confirmation from both doctor and patient demonstrating that palliative care options were offered, explained, and made available to any patient requesting MAiD prior to the doctor approving the patient for MAiD.

- Provincial governments, in partnership with local health authorities, should develop Visitor Access Policies unique to palliative and hospice care that ensures family and friends will have access to their loved one throughout the stages of dying. Accommodation for visits from spiritual leaders or chaplains should also be prioritized.

- Provincial governments should make use of super tax credits or donation matching programs to support independent and mission-driven palliative care initiatives, such as those founded by cultural or religious groups. This facilitates citizens who wish to die in a setting that understands, respects, and honours their spiritual beliefs and commitments or cultural identity and practices.

- Provincial governments should designate a minimum number of palliative care beds in all hospitals, based on hospital and community size, to immediately increase access to and attention on palliative care. A minimum of one “cuddle bed” should be mandatory at all facilities that provide palliative care. Provincial governments should also consider funding rental of these cuddle beds for in-home end-of-life care, to allow families to maintain physical connection with their loved one.

- Provincial governments should create specialized palliative care consultation teams in all hospitals and communities.

Endnotes

[i] Access to Palliative Care in Canada. Canadian Institute of Health Information Report, 2018, p. 10.

[ii] World Health Organization’s Key Facts on Palliative Care, August 2020; See also the Government of Canada resource on Palliative Care.

[iii] Throughout this report, the term “MAiD” will be used, only because it is the common term used in Canadian public policy and law. However, we object to the term as intentionally misleading and profoundly euphemistic, blurring the lines between the categorically different areas of palliative medicine (which gives aid to people for as long as they live in order to help them die well) and assisted suicide (which intentionally hastens death by assisting a patient to prematurely end their life when the patient express a wish to die).

[iv] Government of Canada’s First Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (2019).

[v] How to improve palliative care in Canada: A call to action for federal, provincial, territorial, regional and local decision-makers. Nov 2016. Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians Report.

[vi] Canadian Cancer Society: Palliative care – Guaranteed right to palliative care for all Canadians. Available online.

[vii] R. Gallagher and M.J. Passmore. May 2020. Canada needs equitable, earlier access to palliative care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(20).

[viii] Access to Palliative Care in Canada. Canadian Institute of Health Information Report, 2018, p. 9.

[ix] How to improve palliative care in Canada: A call to action for federal, provincial, territorial, regional and local decision-makers. Nov 2016. p. 8; Report from the Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians.

[x] Fact Sheet: Hospice Palliative Care in Canada. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2020. The numbers used in this report are generous – some sources cite nationwide access to be less than 20%. See also Access to Palliative Care in Canada, 2018, pp. 6, 14. Canadian Institute of Health Information Report.

[xi] Right to Care: Palliative care for all Canadians (2016). Report from the Canadian Cancer Society.

[xii] Access to Palliative Care in Canada, 2018. Canadian Institute of Health Information Report.

[xiii] Paul Adams, “What my dying wife and I never knew about palliative care.” July 2017. Available as an Ottawa Citizen article and on eHospice.com.

[xiv] Palliative Care in Canada Inconsistent, Patients Say. Canadian Institute for Health Information (2018).

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Herx, L. (2015) Physician assisted death is not palliative care. Current Oncology; 22(2), 82-83.

[xvii] Not her real name. Story shared along with others citing the use of MAiD without adequate palliative care as a medical error in: Gallagher, R., Passmore, M. and Baldwin, C. (2020). Hastened death due to disease burden and stress that has not received timely, quality palliative care is a medical error. Science Direct, Vol 142.

[xviii] Ruth Dick, “Replacing Aid with MAiD.”Published on Convivium.ca on March 29, 2021.

[xix] Health Canada (2018b), as cited in Fact Sheet: Hospice Palliative Care in Canada. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2020.

[xxi] Exodus 4:11; Romans 8:18-21

[xxiii] Psalm 139:16; Psalm 90:12-16

[xxiv] Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day 1

[xxv] See Romans 8:31-39

[xxvi] Isaiah 53:1-12; Hebrews 4:14-16

[xxvii] Revelation 21:4 (NIV): “He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” See also Psalm 56:8 (NLT): “You keep track of all my sorrows. You have collected all my tears in your bottle. You have recorded each one in your book.”

[xxviii] Genesis 9:6; Exodus 20:13

[xxix] Matthew 5:21. See also Romans 12:20; 1 Peter 3:8; Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day 40.

[xxxi] Compassionate Communities in Canada: Fact Sheet on Compassionate Communities from Pallium Canada.

[xxxii] Statistics Canada. Deaths, by place of death (hospital or non-hospital). Date range: 2015-2019

[xxxiii] Health Care Use at the End of Life in Western Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007, p. 22.

[xxxiv] Government of Canada’s Action Plan on Palliative Care: Building on the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada. Updated October 29, 2019. See also Canadian Institute of Health Information’s Access to Palliative Care in Canada (2018).

[xxxv] Access to Palliative Care in Canada. Canadian Institute of Health Information Report, 2018, pp 23-24.

[xxxvi] Cost Effectiveness of Palliative Care: A Review of the Literature. The Way Forward Initiative Report: An Integrated Palliative Approach to Care (2013).

[xxxvii] Ibid, p. 37

[xxxviii] Blueprint for Action: 2020-2025. Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada: A Progress Report. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association.

[xxxix] Canadian Virtual Hospice: Excellent online resources for all Canadians.

[xl] This dollar-for-dollar donation match approach was taken, for example, in response to the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. The government recognized the desire of Canadians to be involved in helping, and matched funds donated to registered, approved charities that were doing relief work in Haiti. Such an approach could be taken through a website such as CanadaHelps.org.

[xli] Statistics indicate that, by 2030, seniors will make up close to one quarter of Canada’s population. The number of Canadians aged 80 and older is expected to double by 2036, to more than 3 million people.

[xlii] Monette, M. (2012) Palliative care training substandard. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(12), 643-644.

[xliii] Innovative Models of Integrated Hospice Palliative Care. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, The Way Forward Initiative: An Integrated Palliative Approach to care (2013).

[xliv] Vogel. L. (2017) Canada needs twice as many palliative specialists. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189 (1), E34-35.

[xlv] Wiebe, E., Shaw, J., Green, S., Trouton, A. and Kelly, M. (2018). Reasons for requesting medical assistance in dying. Canadian Family Physician 64(9), 674-679. Also see Li, M., Watt, S., Escaf, M., Gardam, M., Heesters, A., O’Leary, G. and Rodin, G. (2017). See also Medical Assistance in Dying: Implementing a hospital-based program in Canada. New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 2082-2088.

[xlvi] Atul Gawande, Being Mortal: Medicine and what matters in the end (New York, New York: Henry Holt, 2014).

[xlvii] Palliative Care in Canada Inconsistent, Patients Say. Canadian Institute for Health Information (2018).

[xlviii] See also a similar recommendation in “Not to be forgotten: Care of Vulnerable Canadians”, an extensive report from the Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care, Nov 2011, p. 34.

[xlix] Monette, M. (2012) Palliative care training substandard. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(12), 643-644.

[l] See for example the work done by Covenant Health Palliative Institute on Alberta Palliative Care Competencies and Frameworks as well as the courses available through Pallium Canada’s LEAP initiative.

[li] Atul Gawande, Being Mortal: Medicine and what matters in the end (New York, New York: Henry Holt, 2014).

For discussion of end-of-life conversations, see for example page 182. Bringing palliative care training to all medical professionals would advance palliative care in that every person would be treated with not only their physical survival in mind, but also their broader well-being, considering patient fears and hopes, the trade-offs they are and are not willing to make, and finding the medical course of action that best serves this understanding (p. 259).

[lii] Lord, B., Récoché, K., O’Connor, M., Yates, P., & Service, M. (2012). Paramedics’ perceptions of their role in palliative care: analysis of focus group transcripts. Journal of Palliative Care 28(1): 36-40.

[liii] Stone, S.C., Abbott, J., McClung, C.D., Colwell, C.B., Eckstein, M., & Lowenstein, S.R. (2009). Paramedic knowledge, attitudes, and training in end-of-life care. Prehospital Disaster Medicine 24(6), 529-534.

[liv] Spotlight on Innovation – Paramedics providing palliative care at home program. Access to palliative care in Canada, 2018, p.16. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pallium Canada also has a one-day palliative care training course available for paramedics called LEAP Paramedics.

[lv] Paramedics providing palliative care at home: A mixed-methods exploration of patient and family satisfaction and paramedic comfort and confidence. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Feb 2019.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Stajduhar, K.I., Giesbrecht, M., Mollison, A. & d’Archangelo, M. (2020) “Everybody in this community is at risk of dying”: An ethnographic exploration on the potential of integrating a palliative approach to care among workers in inner-city settings. Palliative and Supportive Care, 18 (6), 670-675. Available online as of May 7, 2020 via Cambridge University Press.

[lviii] Equity in palliative approaches to care. PORT: Palliative Outreach Resource Team. Accessed online March 3, 2021.

[lix] Palliative Care. World Health Organization summary, accessed online June 2, 2021.

[lx] Innovative Models of Integrated Hospice Palliative Care. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association: The Way Forward Initiative: An Integrated Palliative Approach to care. (2013).

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Otani, H., Yoshida, S., Morita, T., Shima, Y., Tsuneto, S. and Miyashita, M. (2017). Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54: 273-279.

[lxiii] Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association calls for more compassionate visitation protocols during COVID-19 pandemic. Press release from the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (2020).

[lxiv] James Downar and Mike Kekewich (2021). Improving family access to dying patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, Respiratory Medicine, p. 1.

[lxv] Mendoza, Marilyn A. (2017) Touching the Dying: Connecting at the End of Life. Psychology Today.

[lxvi] Clohessy, K., “Cuddle beds help dying patients feel less alone.” Seven Ponds blog (2019). See also Ashley Field’s Global News report: “Bridgewater woman wants to see cuddle beds in N.S. hospitals in honour of late hug-loving husband”(2020), “A Cuddle Bed for Palliative Care,” an ongoing fundraising effort in Newfoundland/Labrador that aims to have cuddle beds in every palliative care facility in the province, and Melissa Tobin’s “Mother’s death inspires effort to buy more cuddle beds for Gander hospital,” CBC News (2017).

[lxvii] See for example Spiritual Health Services through British Columbia’s Fraser Health Authority.